Re-Cycle: ‘A whole world of sensations’: When Eduardo Chozas conquered Claudio Chiappucci in Sestriere

/dnl.eurosport.com/sd/img/placeholder/eurosport_logo_1x1.png)

Updated 09/09/2021 at 13:53 GMT

Spaniard Eduardo Chozas denied Italy's Claudio Chiappucci in the Giro d'Italia's first ever summit finish in the ski resort of Sestriere in 1991 – 14 months before El Diablo soloed to victory on the same climb in one of the most magnificent breakaways in Tour de France history. Felix Lowe recalls a story of two summit finishes.

Eduardo Chozas

Image credit: Getty Images

Having revisited Marco Pantani's swashbuckling victory at Madonna di Campiglio – and subsequent disqualification and downfall – in the 1999 Giro d'Italia, Re-Cycle winds the clock back another eight years to another Italian climber snubbed reaching for the clouds.

Claudio Chiappucci's name is synonymous with Sestriere. But a year before the Italian climber broke away to his legendary Tour de France stage win in the Italian ski resort, he came off second best in a test run during the 1991 Giro d'Italia.

The man who beat him? Eduardo Chozas, a 30-year-old Spanish climber who, that year, would join the elusive club of riders to have finished in the top 20 of each of cycling's Grand Tours in the same season.

Now a Eurosport pundit in Spain, Chozas capped a fine team performance – as part of an ONCE squad that included 1982 Vuelta champion Marino Lejarreta –to secure the seventh and last Grand Tour stage win of his career. He did so after a challenging double ascent of Sestriere, staving off a late surge by the man they called ‘El Diablo’ in Stage 13 of the 74th edition of La Corsa Rosa.

Denying Chiappucci in front of hordes of Italian fans on the famous climb, Chozas put the celebrations on ice for the disappointed tifosi, who would return to the climb in their droves during the following year's Tour to see their man emerge from the footsteps of the great Fausto Coppi.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2017/09/11/2165336-45264130-2560-1440.jpg)

Eduardo Chozas, con el equipo Reynolds en los años ochenta

Image credit: Eurosport

In the tyre tracks of Il Campionissimo

Its proximity to the border with France means the Colle Sestriere is one of the rare climbs used frequently in both the Tour and the Giro – dating back to 1911 when it made its bow in the third Giro. Lucien Petit-Breton, the Frenchman raised in Argentina, led over the summit en route to becoming the first non-Italian stage winner in the race's history.

In 1949, Coppi gobbled up the climb during his majestic Stage 17 win between Cuneo and Pinerol. Three years later, he capped his epic 190-kilometre solo break with victory on the Tour's first ever summit finish at Sestriere, two days after the irrepressible Italian had triumphed on the race's inaugural ascent of Alpe d'Huez.

The climb also provided the canvas for one of the best career victories for Franco 'Crazy Heart' Bitossi in 1964, when the Italian broke clear of compatriots Vittorio Adorni, Gianni Motta and the eventual Giro winner that year, Jacques Anquetil, in the closing kilometres.

As the journalist and author Chris Sidwells says of the Colle Sestriere, with its three possible ascents – two from the west and one from the east: "It's not a long one, nor particularly hard, but iconic because of its strategic location and because of the men who made it so."

Other champions to raise their hands aloft over its summit through the years include Miguel Induráin, Bjarne Riis, Andy Hampsten, Lance Armstrong, José Rujano, Alberto Contador, Fabio Aru and… Vasil Kiryienka. Not to forget, of course, the colourful Chiappucci. But before "Chiappi" outdid Coppi with a breakaway even more incredible than the great man’s 190km effort, he was held at bay by Chozas.

Setting the scene

The big favourite for the 1991 Giro was the dark, handsome and chiselled defending champion Gianni Bugno, who cited compatriot Chiappucci as his biggest rival. Twelfth in 1990, Chiappucci had gone on to finish runner-up in the Tour the previous summer, coming within one day and a botched time trial of denying Greg LeMond his third Yellow Jersey in Paris.

Without a podium place all year, LeMond was also on the start list at the 1991 Giro, the American insisting before the Grande Partenza in Sardinia that he intended to be more competitive in Italy than in years past, despite riding primarily in preparation for July's Tour. If not full-on beef, then there was certainly a thin slither of bresaola between LeMond and the rider he dismissively called "Cappuccino".

Owing his stint in yellow in 1990 to getting in an opening day break that gained more than 10 minutes on the big guns, Chiappucci was viewed by many as a bit of a happy-go-lucky chancer, most notably by LeMond, who famously described him as "nothing more than a bandit". His inability to race against the clock forced him to become a fearless aggressor who needed long-range breaks to get in the mix.

Truth be told, Chiappucci's attacking instinct might have made him popular with the fans, but it hardly endeared himself to his rivals. A sweet talker who reportedly put three spoons of sugar in his breakfast muesli, the diminutive Italian was viewed as chippy, notoriously tight-fisted and, on the bike, a law unto himself; he once came to blows with compatriot Moreno Argentin, who grumbled that he "had the legs of a champion but the mind of a child".

In any case, Chiappucci was doing his utmost in 1991 to prove that his breakout Tour was no fluke. The 28-year-old Carrera ace had taken a leaf out of Bugno's book by winning Milan-San Remo after a long, lone breakaway. His stonking spring continued with victory in the Basque Tour and a podium place in the Flèche Wallonne.

But when the Giro got going in May, it was neither Chiappucci nor Bugno – and certainly not an out-of-sorts LeMond – who set the early agenda. It was the Italian Franco Chioccioli of the Del Tongo-MG Boys team. The 31-year-old had still not got over losing his Maglia Rosa to Andy Hampsten on the snowy Gavia Pass in 1988 and was riding the race of his life.

Nicknamed "Il Coppino" – the Little Coppi – because of his resemblance to the campionissimo, Chioccioli was in pink when the race hit mainland Italy after the opening three stages in Sardinia. Eric Boyer, the Frenchman on LeMond's Z squad, had wrestled the jersey from Chioccioli for one day. But the Italian was back in the driving seat after Marino Lejarreta, the Spanish leader on Eduardo Chozas' ONCE team, won a hilly stage in the Abruzzo.

But a blistering time trial by Bugno on Stage 10 saw the revived defending champion come within one second of Chioccioli's overall lead, with Chiappucci 56 seconds down in fourth, behind Lejarreta, and the languid LeMond more than three minutes in arrears.

Suddenly, the pack was stacked in Bugno's favour. Until, out of the blue, Bugno cracked on the Stage 12 hilltop finish on Monte Viso, shipping two minutes on the first day in the Alps as Chioccioli consolidated his lead. On the eve of the stage to Sestriere, his nearest rival was now Lejarreta, 30 seconds adrift, with Chiappucci in fourth a further minute back.

Stage 13, Giro d'Italia 1991

The second day in the Alps culminated with a double ascent to Sestriere – a twin bonanza for the Giro's first ever summit finish at the ski resort situated 2,035m above sea level in the Val Susa, sixty Roman miles from Turin (hence its name).

This is where our man Eduardo Chozas enters the story. The Spaniard had been playing a support role for teammate Lejarreta in what was his 23rd Grand Tour, having arrived in Italy off the back of an 11th place finish in the Vuelta. Still following the old season schedule, the Vuelta – in which Lejarreta had finished third behind compatriots Melchor Mauri and Miguel Induráin – had come to an end just one week before the Giro's opening stage.

In the previous day's opening chapter in the Alps, Chozas supported his team leader before dropping back to take a solid seventh place – a minute behind Lejarreta and Chiappucci. While no threat to the GC, Chozas still lurked in 15th (7'22" down) and was keen to leave his mark on the race.

"The mountain stages were my goals to try for stage wins," Chozas tells Eurosport. "Preferably those of the first half of the Giro, since I had ridden the Vuelta and I knew that the last week was going to be very hard for me due to the accumulation of fatigue."

A break of 12 went early in the stage and included Chozas' ONCE teammate Luis María Díaz de Otazu. The gap was never very large, forcing ONCE to make their move after the first ascent of the Colle Sestriere – with Chozas zipping clear in the wake of another rider after an earlier softener from teammate Santos Hernández.

“The break did not have much advantage, so I was very attentive to the moves on the final ascent,” says Chozas. “When an Italian cyclist attacked at the beginning of the final ascent, I went after him and opened up a gap on the peloton.”

Chozas quickly passed the remnants of the break and, surging through the pine forest to bring the snow-clad peaks into sight, he soon joined up with Hernández and the Mexican Miguel Arroyo of LeMond's Z team on the front of the race.

Behind, it was Chiappucci in the Maglia Ciclamino who set the tempo in the group of favourites, flanked by Chioccioli in pink and Lejarreta in the eye-catching yellow ONCE jersey – the one that changed colours to pink during the Tour to avoid confusion with the maillot jaune.

ONCE were playing a blinder – the kind of move you expect to see, say, from a modern-day Movistar in the Vuelta – with two men ahead and their leader in the wheels of his rivals a bit further down the mountain. The stage was theirs to lose.

A few kilometres from the summit, the gap between the two groups hovered above the minute mark as Chiappucci continued a long, unseated surge on the front, his purple jersey and those trademark blue Carrera shorts elegantly offset by his tanned arms and yellow helmet (hearts-in-eyes emoji).

"When I came to the front, I started to set the pace, but I saw that it was better to stick with Arroyo for the time being and let my teammate attack," Chozas says.

As Hernández surged clear off the front, Banesto's Pedro Delgado put in the first move from the pursuing group of favourites, the 1988 Tour de France winner riding in what was only the second Giro appearance of his career.

Delgado was joined by the Frenchman Eric Boyer before both riders were reeled in when Chiappucci, Chioccioli and Lejarreta threw the hammer down to distance the struggling Bugno, knocking another nail into the coffin of the defending champion. With sparks flying behind, it was time for Chozas to make his decisive move:

"I stayed on the wheel of Arroyo for 500m and then dropped him with an attack before rejoining my teammate ahead. There were just two kilometres remaining, but our gap on the Chiappucci group was not big."

Chozas and Chiappucci were not so much two peas in a pod as an apple and an orange in the large colourful fruit salad that was the pro peloton.

Calimero, Andreotti, Mondon, Chiappi, Motopertuto, Indiano: these were all nicknames bandied around for the flamboyant 28-year-old Chiappucci. He even liked to call himself 'The Bionic Man' before finally settling on the one that stuck: El Diablo.

But the reserved Chozas had no need for such nominal accoutrements. "I had no nickname," he explains. "My surname is rare enough as it is."

And while Chiappucci had won a stage and finished runner-up to LeMond in Paris in 1990, making him a household name in Italy, Chozas had been a consistent performer in Grand Tours over the years, picking up four Tour stage wins and two Giro successes despite never cracking the top five on GC.

In fact, Chozas had secured his second Tour stage win – at Serre Chevalier in 1986 – in way that would become typical of Chiappucci: a break of 150km and a winning margin of six minutes over LeMond in yellow.

"I knew Chiappucci well and watching the images back today it's clear that he was the strongest of my pursuers," Chozas says. "He was so fast on climbs like that and the final kilometre was agony for me to hold on to my advantage, which came down to just 15 seconds. I was listening to the tifosi cheer on Chiappucci. The fans were so close and I didn't know how I could get the strength to hold on until the end. I was almost over the limit and it was my mind that made me overcome the difficulties and hold on."

The most beautiful victory

Having kicked clear of teammate Hernández before the flamme rouge, Chozas could practically feel the chasing trio breathing down his neck. Constantly looking over his shoulder and putting in surges out of the saddle, the Spaniard dug deep through the sea of Italian fans to hold on for the third – and hardest fought – Giro win of his career.

Had the finish been just 50m further, Chiappucci could well have picked up a maiden Giro stage win – the Italian eventually crossing the line just one second behind a relieved Chozas. Lejarreta and Chioccioli arrived two seconds back, with Hernández settling for ninth place to give ONCE three riders in the top 10 after a near-perfect collective day in the saddle.

"Even when I watch it on video now, I get goose bumps because it was such a nail-biting finish,” says Chozas. “It's very nice to see as a fan and, for me, remembering the effort I had to put in, the screaming of the fans, the deafening sound of the helicopter above – it was a whole world of sensations that culminated with an explosion of joy winning at the top of Sestriere."

The nature of the win made it the most memorable of Chozas' career. "My most important win was the legendary stage in the 1986 Tour with a finish on the Col du Granon in Serre Chevalier when I won after a 150km break, passing over the Col de Vars and Col d'Izoard in pole position," he says.

"That day I finished more than six minutes ahead of LeMond and 10 minutes clear of Bernard Hinault. But this stage in Sestriere was just spectacular. With the good weather and crowds on the climb, for me it was the most beautiful and spectacular victory I ever achieved."

Spanish newspaper El País celebrated "the exhibition" laid on by Chozas and his ONCE team, capped by Lejarreta sticking with the two Italian favourites to retain his second place on GC, 26 seconds down on Chioccioli.

If these three riders confirmed their status as the main contenders, the paper noted the significant deficits conceded by the likes of Bugno and Delgado, adding the following damning verdict: "Already merely anecdotal is the disadvantage of other illustrious riders who have already lost all hope of a high finish – such as the American Greg LeMond and Frenchman Laurent Fignon."

The paper quoted ONCE directeur sportif Manuel Sáiz, who claimed his main concern now was Chioccioli, "because he is showing that he is capable of responding on the mountain and because it seems that Bugno is not at his best".

What happened next

Sáiz was right to fear Chioccioli most of all, for it was the Italian who held on to the Maglia Rosa in swashbuckling style, winning three stages – two in the Dolomites and the final time trial – and beating Chiappucci by almost four minutes in Milan. An all-Italian podium was completed by Max Lelli, with Bugno, despite a consolatory Stage 19 win, a distant fourth almost eight minutes in arrears.

Having won the 1991 Giro in commanding fashion – capped by the ITT in which he flattened everyone, taking almost a minute off Bugno – Chioccioli begged the press to stop calling him Coppino. But they were having nothing of it. As for Bugno, he would turn things round later that year with victory in the World Championships in Stuttgart, doubling up a year later in Benidorm.

As for the gutsy Lejarreta, his pursuit of pink was undone by a crash on Stage 17 on a day Fignon joined LeMond (who had already quit the race) and withdrew. After shipping six minutes, the 34-year-old Lejarreta dropped to fifth place in the final standings, with Chozas himself coming home in 10th.

If LeMond's poor performance might have given Chiappucci a boost for the Tour de France, the irrepressible rise of Spanish juggernaut Miguel Induráin put paid to any such wishful thinking.

LeMond wore the Yellow Jersey for four days but eventually finished seventh, while El Diablo won a stage and took the Polka Dot jersey, but finished almost six minutes behind in third place as Big Mig took the first of his five successive Tour wins by 3'36" over Bugno.

That man Induráin won the next time the Giro returned to Sestriere – in a gruelling 55km time trial from Pinerolo that provided the cherry to the first tier of the cake that was the Spaniard's second Giro-Tour double in 1993.

Chiappucci, never the best against the clock even on an uphill parcours (and with a cartoon devil on his helmet), finished four minutes down that day. But a year earlier, El Diablo had turned around his narrow loss to Chozas at Sestriere by recording one of the most staggering wins in cycling history.

Chiappucci’s Sestriere cheer

Forty years after Coppi's signature win in Sestriere, Chiappucci raised his hands aloft in the ski resort during the 1992 Tour after a solo break of six-and-a-half hours during the brutally mountainous 254.5km stage 13 from Saint-Gervais.

With the stage finishing in his native Italy and on a climb synonymous with Il Campionissimo, Chiappucci targeted this as an opportunity to showcase his aggressive and unpredictable style against the steady, stoical, metronomic suffocation of the unflashy but clinical Induráin.

El Diablo attacked on the Col des Saisies, the first climb of the day, 245km from the finish, ostensibly in pursuit of the KOM points that would help consolidate his Polka Dot Jersey. He then kicked on at the foot of the Cormet de Roselend, taking nine riders with him.

Chiappucci tackled the next climb, the 37km Col d'Iseran, the highest pass in the Alps, as if it were the final ascent of the day, with only Frenchman Richard Virenque able to hold on. With snowdrifts either side of him, the Italian went over the top two minutes clear of Virenque, causing carnage in his wake – with LeMond, a Ferrari in the face of Induráin's diesel-powered SUV, almost 20 minutes adrift.

With Induráin and Bugno in pursuit, Chiappucci held on over the summit of Mont-Cenis before securing what the author Richard Moore, in his book Étape, describes as "one of the most extraordinary, almost unbelievable, performances in Tour history".

It was a victory that Chiappucci later put down to "lots of passion, stubbornness, suffering and willpower," glossing over the additional boost most riders of that generation enjoyed. Chiappucci later pointedly admitted to an Italian prosecutor that he had used EPO since 1993 – the year after Sestriere.

The next day, Chiappucci's win was made even sweeter when LeMond, the man who once dubbed him "Cappuccino", withdrew during the stage to Alpe d'Huez after being spat out the back on the Galibier. The American's departure came as little surprise given he had finished in the gruppetto in Sestriere over 42 minutes down on El Diablo.

Asked by Moore whether that brought a smile to his face, Chiappucci said: "I was already finished with him. After the 1990 Tour, he just didn't exist in my book. But it gave me a bit of pleasure to force him out, yeah."

The man who held him off in Sestriere a year earlier was happy to see his friend pull off such an emphatic victory at the same summit.

"I really liked that he won because he was very brave and a very good rider," Chozas says. "I also got along very well with him – we had become good friends in his first Giro appearances where we escaped together in various stages, and he was one of the first to congratulate me after my victory in 1991."

Chiappucci might have won the battle at Sestriere in 1992, but the deadly Induráin won the war to secure a second successive Tour by more than four minutes on El Diablo. It was the third Grand Tour out of four that saw Chiappucci finish bridesmaid to the polygamous pedaller from Spain. In 1993, Chiappucci finished third in the Giro as Induráin won a second successive Maglia Rosa ahead of his third Tour win.

For all his pizzazz, Chiappucci never won a Grand Tour – despite a run of six races finishing on the podium. All this, while still living at home with his mother, who made vests that his family sold in a small textile shop and at local markets in Lombardy.

"The vests are of a very good quality flannel," he once said. "They are not white, they're buff, but they are very warm and absorbing. Stephen Roche orders them all the time, and several other riders wear them."

As for Chozas, he never wore a Chiappucci vest, and he never won another Grand Tour stage either. His Sestriere success the 17th and final notch in his career bedpost. Two months later, though, both he and Lejarreta rode the Tour – their third of the season – with Chozas the best-placed ONCE rider in 11th, exactly 21 minutes behind Induráin.

Chozas became only the fifth rider in history to finish in the top 20 of all three Grand Tours in the same season after Raphael Geminiani (1955), Gaston Nencini (1957), Federico Bahamontes (1958) and his teammate Lejarreta (1989). It would be another 19 years before this feat was repeated, by Carlos Sastre in 2010.

Chozas retired in 1993 aged 33 after two more Grand Tours – taking his career tally to 27, of which he completed 26. It would be another record not matched until Matteo Tosatto in 2015 after the Italian also completed 26 Grand Tours. Tosatto would add two more before his own retirement, finally completing 28 of his 34 Grand Tours – more than anyone in history.

Does Chozas perhaps now regret not finishing the 1984 Vuelta, which he quit on the final day?

"I didn't start the last stage because I was not feeling very well for a few days and I had to go to the Giro afterwards," he says. "At the time, I didn't think much of it, but perhaps now with the perspective of time it would have been wiser to finish the easy final stage to make it 27 out of 27."

One thing that is certain is that Chozas will be watching stage 20 of the 2020 Giro – should it ever take place – with added interest following his beautiful win in Sestriere. Not only will the Colle Sestriere be the final and perhaps deciding climb of the entire race, Chozas will be drawing on his experience as a pundit for Spanish Eurosport.

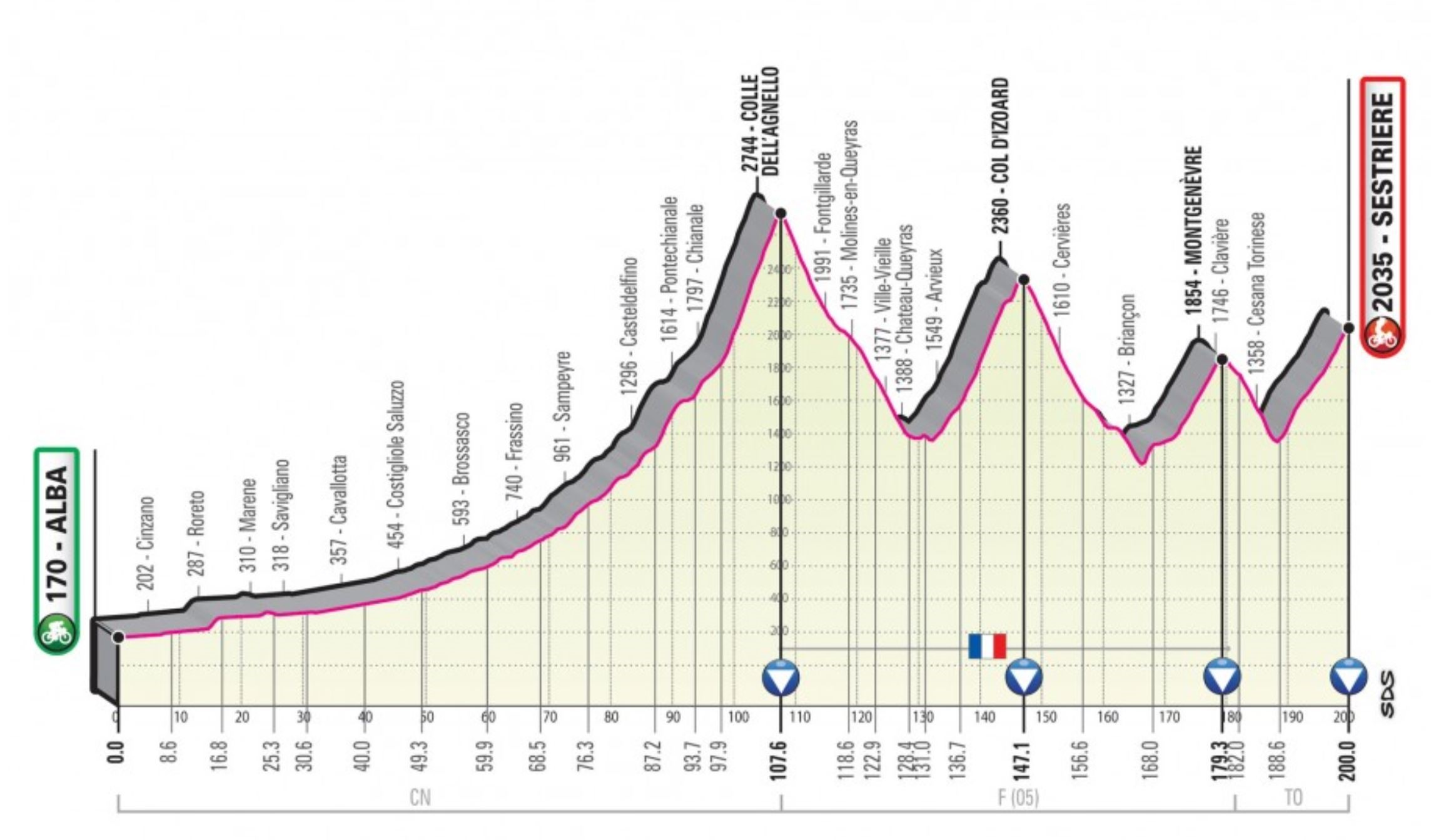

"An arrival in Sestriere will always be an important stage of the Giro," he says of the 200km test, which also features the Colle delle Agnello, the Col d'Izoard and Montgenèvre. "With a hard profile and many Alpine peaks of considerable hardness, only one of the best climbers of the Giro will win. I have always followed the arrivals at Sestriere very carefully since my victory because the winners are usually heavily linked to the history of cycling."

A victory in the vein of Chozas in 1991 or Chiappucci one year later would make stage 20 of this season’s Giro d'Italia rather special. Whenever – if ever – it happens.

Scan me

Related Topics

Share this article

Advertisement

Advertisement