The Essential Olympic Stories: Anton Geesink and Japan's tears of silence

THE ESSENTIAL STORIES – When the Olympic Games were first held in Tokyo, in 1964, the Japanese only had eyes for judo, which was being included as an official sport for the first time. Japan's judokas were tipped to pull off a clean sweep of four gold medals – but a giant Dutchman blocked the hosts' way, writes Laurent Vergne.

Sponsored by

Bridgestone:focal(1265x722:1267x720)/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2023/08/24/3768965-76669228-2560-1440.png)

Anton Geesink and Japan's tears of silence - The Essential Olympic Stories

This was how Anton Geesink plunged an entire country into unimaginable despair by winning the prestigious open weight division judo gold.

- - -

"Help me, Anton." Noël van 't End is not a believer. Not in the religious sense of the word. But that day, he needed convincing of the power of the innermost forces of the spirit. It was August 29, 2019. From awakening at 8 a.m. through to his final fight – a showdown which would hoist him onto the top of the world – the Dutch judoka felt inhabited by the presence of his predecessor.

Budokan Hall in Tokyo is the Mecca of judo, a temple erected for the Tokyo Olympic Games of 1964 which will once again host the judo events for the upcoming Summer Games. Two years ahead of this Olympic reunion, the Nippon Budokan, an eye-catching octagonal structure still boasting its original architectural features, was hosting the 2019 World Championships. "When I entered the Budokan," Van 't End recalls, "there were posters of Anton Geesink everywhere. I could almost feel his presence, like vibrations. So, before each fight, I asked him to help me. Especially before the final."

When he took to the tatami with a World Championship gold medal at stake, Van 't End was following in the trailblazing footsteps of his compatriot Geesink. 35 years on, he, too, was facing a Japanese judoka in front of an expectant home crowd.

I closed my eyes and asked Anton for help one more time, to beat a Japanese guy in the final, just like he did.

In defeating Shoichiro Mukai, Noël van 't End won the Netherlands a first world title in 10 years. He remains convinced to this day that he was carried by the spirit of the legend from Utrecht. "Anton was here with me, the whole day," he says.

An epiphany, aged 14

This time round, when Van 't End won gold, Japan did not shed a tear. While it remains the leading nation in world judo, it has at least learned to share the spoils. Mukai's defeat on home soil was a disappointment but not a national drama. But during the Tokyo Olympics 55 years previously, it was a different story. Back then, one man – albeit a man of Anton Geesink's towering stature – managed to bring a whole country to its knees.

That autumn evening in 1964, the giant Lowlander not only cemented his place in the pantheon of judo and the Olympics, he changed forever the face of his sport and achieved iconic status in the Netherlands. If that is easy enough to believe, then Geesink was also elevated to the rank of quasi-god in Japan despite the national mourning that ensued. This was the full extent of his dual tour de force. And his death in 2010 at the age of 76 elicited comparable emotions in both countries.

Anyone spending a day in Utrecht cannot miss the imposing bronze statue of one of the city's most famous figures. Anton Geesink even has a street named after him – the very same street where he was born, in 1934. As a gangly teenager, he worked in his spare time as a mason. But sport was already his passion: football, swimming, athletics – you name it; Anton dabbled in everything. Until the epiphany. "One day," he said during a French television report devoted to him in 1962, "I attended a demonstration made by a French judoka. I knew that this was what I wanted to do. I was 14 years old."

Pulling up trees

This was the beginning of a very special bond that tied him to France. It was in Paris, only four years after his first steps on the tatami mats, that he won the first of his 21 European champion titles. And it was once again in the French capital that he became, almost a decade later, a world champion, in the first earthquake that would shake the foundations of the sport.

For Anton Geesink, France was also synonymous with training. He spent all his summers at Beauvallon, in the Bay of Saint-Tropez, near the famous seaside resort. Here, at the Camp du Golf Blue, the cream of European judo would meet up to combine relaxation with hard work. It was at this retreat that Geesink forged ties with two great figures in French judo, who were not only his main European rivals but also two close friends: Henri Courtine and Bernard Pariset.

Eric Pariset, Bernard's son, has still not forgotten this man mountain, who seemed as wide as an ox when they met at the end of the 1950s. "The four-year-old child that I was had no idea about the ins and outs of professional judo," he wrote on his blog. "But looking back, this giant impressed me as much by his height as his muscles, his determined face and his very deep voice. In short, I found him fascinating."

For Henri Courtine, it was Geesink's incredible capacity for work which made him stand apart. From his front row seat, he saw it all. "Anton Geesink is said to have won thanks to his extraordinary physique, but his true strength lay in his thoroughness," he told the magazine L'Esprit du Judo. "He never took a break. At summer camp, he was always first to bed and then, the next day, he would rise at 6 a.m. to swim across the bay! And all morning, he would train with logs on the spot." For the giant of Utrecht never lifted weights: his thing was to head into the Massif des Maures and lift tree trunks.

Pariset (whom Geesink once described as his "hardest opponent outside Japan") and Courtine managed to compete for a few years with the colossus. Then, towards the end of the decade, the Dutchman emphatically cast his contemporaries in the shade. As Courtine recalls:

Until 1958, he was still within reach. But after the European Championships in Barcelona, we all felt that he had passed a milestone. From that point, we stood no chance. I don't regret the prizes I may have won had I not had to fight him. In fact, my best memory of competition will always remain the time I once managed to put him on his backside.

Michigami, the encounter of a lifetime

Truth be told, after 1955 nobody would beat Anton Geesink in competition at European level. His horizons had now stretched to include the rest of the world. This was timely, for the first-ever edition of the Judo World Championships took place in 1956. In Tokyo, of course. Weight categories did not yet exist and there was just one tournament open to all sizes. Geesink was still only 22 years old. He made it to the semi-finals where he lost to the champion elect, the Japanese Shokichi Natsui, before beating Courtine to the bronze medal. His hour had not yet come.

It was around this time that Geesink started collaborating with the man who would change his life. The master Haku Michigami, who had lived in France for years and would become the driving force in the globalisation of judo, was appointed in the middle of the 1950s as special adviser to the Dutch judo federation. In the uncut diamond Geesink, Michigami saw an opportunity to "shape a model judoka," as he later told the Japanese journalist Kazunori Iwamoto.

Young Anton was not yet the imposing titan that everyone would soon know. He still weighed only 82 kilograms. "He had a big head and a long neck on a slender, elongated body. To me he looked like a bottle of beer," Michigami recalled. But he, too, would discover that his pupil was a true grafter.

Michigami again: "What struck me about him was the seriousness of his character. The Dutch are known for being serious people, diligent and hardworking, but here he surpassed his compatriots considerably. If he were ordered to run, he would run three times farther than the others. If you did not tell him to stop his uchikomi training, he would have continued all night. Thanks to this regime, his thin neck and slender body soon bulked up."

Paris, the first shockwave

Before the cataclysmic explosion of Tokyo '64, the first seismic shudder struck in the spring of 1961 during the third edition of the World Championships. At Stade Pierre de Coubertin, Geesink completely steamrolled his opponents, including the Japanese, and in the final he dominated the defending champion, Koji Sone. This first stone cast into the Japanese garden was a warning sign three years ahead of the Tokyo Games where, at the host's behest, judo was going to feature on the Olympic program for the very first time.

A few months after this breakthrough triumph, the Dutchman twisted the knife in the wound he'd already inflicted, flagging up the overconfidence of his rivals. "I think that the Japanese arrived in France with big heads. They thought they were very, very strong but after the very first fight, we could see that the Japanese judokas were not athletes. They work only in judo, only in technique, whereas we work hard outside judo."

But on top of his outspoken tirade against Japanese judo, the new world champion did not baulk at questioning his own limitations. This self-awareness was another of his strengths. For instance, he was very critical of his performances at Coubertin despite his gold medal. "After this victory," he explained, "I realised that my judo was not yet mature enough, especially when it came to my ground technique. So I went back to work again twice as hard."

Geesink spent three months in Japan at Tenri University in Nara, where he worked uniquely on his Ne-Waza, or ground technique, which he viewed as the judo of the future. Geesink would later write in one of his 11 books that ground technique was considered minor by many Japanese judoka purists. "They are – in my opinion – too romantic with their insistence on deciding the contest by a spectacular throw." It was at Tenri, in the mythical home of judo, that the Dutchman fine-tuned his craft with sweat and hard work alongside some of the best judoka in the world.

In becoming the first non-Japanese athlete to win in any weight-class in a World Championships, you'd have forgiven Geesink for having got a little big-headed himself. After all, the victory made him a national hero: he was paraded through the streets of Utrecht in a convertible and the city even offered to build him an extension on his house for free. For anyone to cope with such attention it required a soul equal in stature to its powerful body. And for Haku Michigami, this was indeed the case: "The attitude of his entourage, which had completely changed, and the excessive attention thrust upon him by the public – all that terrified him. This showed a glimpse of the kind of man he was."

Spiritual requirement

All that remained was for Geesink to conquer Mount Olympus. Only when it came to winning titles at least. Because medals were not the sole essence of Haku Michigami's quest.

What prompted me to train judokas abroad was certainly not to make them win titles. If I had moved across oceans to the other side of the world, it was because I was inspired by the desire to make people grasp the spirit of authentic bushidō, the Japanese way of the warriors from ancient times.

Geesink had shown his mentor that he was more than capable of overturning the sporting hierarchy to install his own samurai supremacy. But could he permanently rise to the spiritual demands of his mentor? This would be the double challenge posed by Tokyo.

In 1964, Geesink was 30 years old. His first Olympic roll of the dice would also be his last. He knew this. The tall redwood of the Oranje kingdom had hoped to feature at the Rome Games of 1960, as part of the Dutch Greco-Roman wrestling team into which he had been initiated (he was indeed a three-time national champion). But the IOC closed the door on him on the rather tenuous grounds of professionalism, given his status as judo instructor and coach. His Olympic game of double or quits therefore came down to that evening at the Budokan.

Scalded by this Dutch power shift in 1961, the Japanese had secured the introduction of weight categories in order to increase their chances of winning medals. Four events were therefore on the program: lightweight (under 68kg), middleweight (under 80kg), heavyweight (over 80kg) and the open division. Japan had won gold in the first three categories. But there remained the most prestigious open, or unlimited weight, division, where the imposing figure of Geesink loomed large. Failure was unthinkable.

The Emperor brings forward his visit

The Dutch writer and journalist Ian Buruma was 13 years old at the time of his illustrious compatriot's Tokyo triumph. A specialist in Japan, Buruma's book The Missionary and The Libertine is a collection of reflections delving into the way the East and the West see each other. Published in 2000, it includes an essay he wrote for the New York Times nine years earlier in which he explained how judo was perceived in Japan in the 60s:

Judo was not just a national sport, it symbolized the Japanese way – spiritual, disciplined, infinitely subtle; a way in which crude Western brawn would inevitably lose to superior Oriental spirit. A loss in the most crucial category would be seen as an offense to this way of life.

Perhaps an indication of the fear that Geesink inspired, the Emperor Hirohito's planned visit to the Budokan was brought forward by one day. On Thursday October 22, 1964 the 124th emperor of Japan showed up at the hall, which, as the epicentre of the Games for the host nation, had been packed to the rafters throughout the four days of competition. It was the day of the heavyweight finals, won by Isao Inokuma, and the day before Geesink's date with destiny.

Geesink's gold-medal fight against Akio Kaminaga that Friday was in fact a re-run. The two judokas had already faced each other in the preliminary phase when, perhaps portentously for the swelling crowds attending the final, Geesink had dominated during a routine victory against the Japanese idol upon whose shoulders weighed the expectation of a nation. But the format of the tournament allowed early losers to progress from the round robin phase, and so Kaminaga, who was hiding a knee ligament injury sustained shortly before the competition, still had a shot at gold.

Kaminaga and Geesink made their own separate ways to the final without any scares. The former even set a record for the quickest victory in the sport's history – in just four seconds against the Filipino Thomas Chi Hong Ong (a record which would last until 1991). Although Geesink was not far behind: in the semi-finals, he needed just 12 seconds to dispatch the Australian Ted Boronovskis.

Despite this promising form, the Dutchman was struggling with anxiety before his final fight. He decided to call Michigami, who was present in Japan with some French students. "Anton let me know, through a third party, that he was worried and wanted me to attend his match," the Japanese master explains. "So, I rushed to the hall where the encounter was taking place and, in this way, I was able to observe closely how it all unfolded."

Kaminaga as helpless as a child

For the gold medal decider, the most important event of the 1964 Games in the eyes of the host nation, Budokan Hall was packed. 15,176 people crammed inside, oscillating between the feverish hope of witnessing a victory for Kaminaga which would complete the collective work of Japan's judokas, and the fear of experiencing a painful but nevertheless historic moment in the event of a win for the gigantic 120kg challenger. Each scenario was capable of causing a wave of emotion.

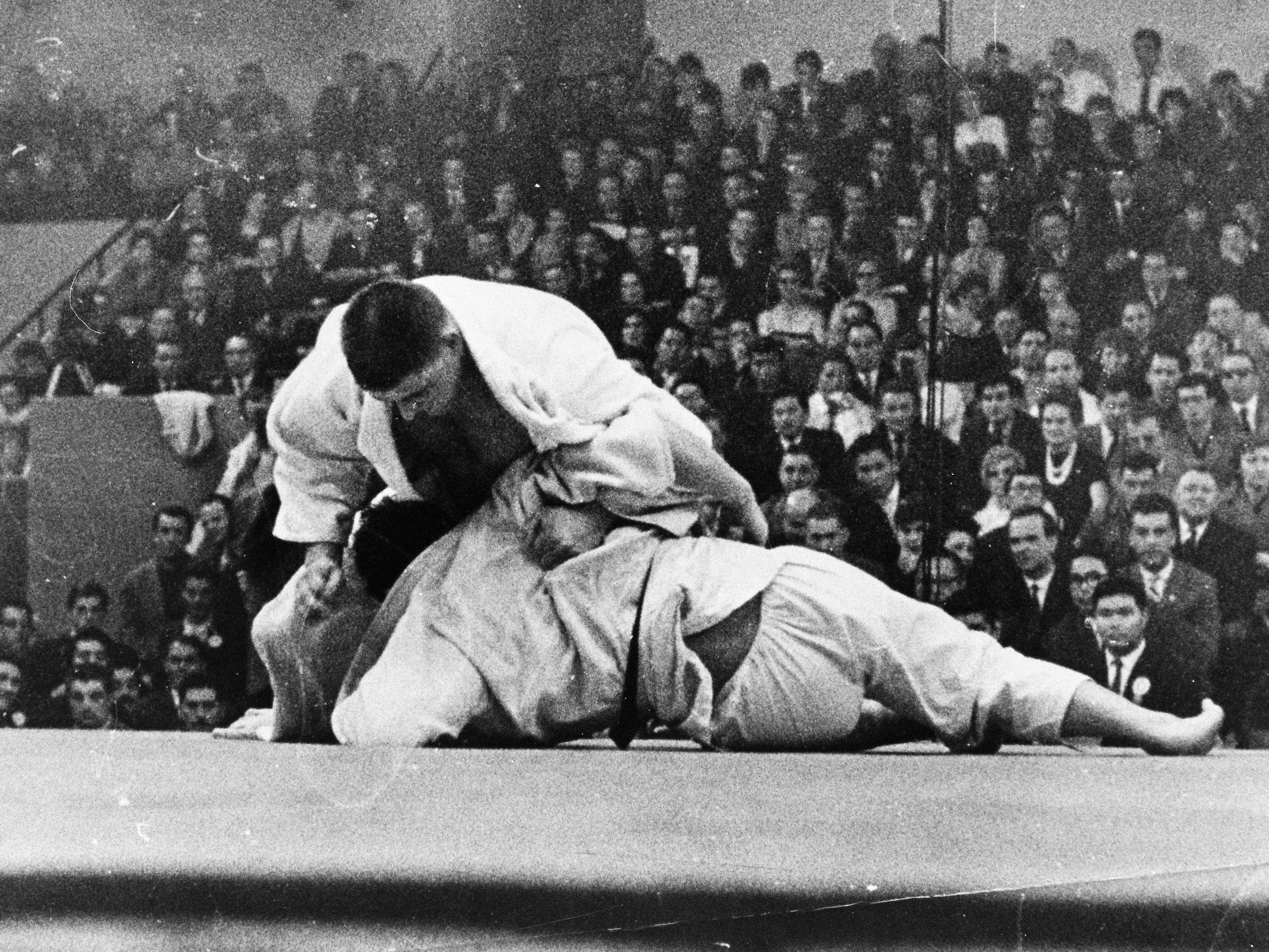

Entering its ninth minute, the fight was tense and on a knife-edge. Taking advantage of a speculative Tai-Otoshi attempt by his opponent, Geesink then flung Kaminaga to the mat, putting himself into a position to conclude with a grappling Hon-Kesa-Gatame scarf hold. To pull it off and become Olympic champion, he needed to pin him down for 30 seconds. Geesink had made ground technique his obsession – and it was here that those months of sharpening his Ne-Waza at Tenri University paid off.

Half a minute seemed to last an eternity. Helpless and immobilised in the grip of the giant, Kaminaga made a desperate effort to extricate himself, thrashing about with his legs as he tried to heave himself up. But he was crushed by the two-metre colossus from Utrecht, who was more than 20kg heavier. Throughout these death throes, Geesink kept his eyes fixed on his prey – as if to better read his agony. Beneath the Batavian's bulk, Kaminaga struggled like a desperate child. But it was all in vain.

The silence which then fell on Budokan Hall left an indelible mark on all those present. The crowd collectively rose to applaud Geesink for a brief moment before sitting back down again. Many burst into tears. In the streets of Tokyo, and all the major cities of Japan, where television screens had been installed in shop windows, dazed spectators were also reduced to tears. An entire country fell into collective shock.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/05/19/3135840-64272528-2560-1440.jpg)

Antonius Geesink (bottom) of the Netherland and Akio Kaminaga (top) of Japan compete in the Judo Open Category gold medal match during Tokyo Summer Olympic Games at the Nippon Budokan on October 23, 1964 in Tokyo, Japan

Image credit: Getty Images

A solar eclipse across Japan

Seventeen-year-old Ada Kok was in the tribunes that day. This young Dutch swimmer, a silver medallist in the 100m butterfly, had been invited by her national federation for an experience that would stay with her forever. As she told The Guardian a few years ago: "It was just a fight to me at the time. But on reflection, I realised I was watching a culture shock of sorts, going throughout Japan. The Budokan was silent. Quiet. I could hear people crying. It was like a solar eclipse had suddenly blackened out all of Japan. It was a feeling of doom."

Everyone who experienced that instant was, like Ada Kok, first struck by the silence that had invaded the hall. Silence and tears.

Geesink himself told reporters that coping with the reaction of the Japanese crowds after the fight had been tougher than the fight itself. Indeed, from a sporting point of view, the result had simply followed the rules of logic. Jim Bregman, a bronze medal winner in the middleweight category for the United States jugo team in the Tokyo Games, remembers seeing all the officials and Japanese members of staff crying in the locker room of the Budokan. But he also felt the hosts had no reason to feel disgraced, describing Geesink as "a technical genius, very powerful, very fast judo player of consummate skill in a very large frame."

Michigami's true pride

Geesink showed exceptional dignity in victory. As during his world title in Paris in 1961, the Dutch entourage sought to invade the tatami to express their joy. But the victor had barely loosened his grip on Kaminaga when his first unequivocal gesture was to order his countrymen to step back and stay on the sidelines. Much more than his coronation, it was this attitude that filled his master Michigami with pride, as he later recounted:

Holding back with a gesture the delirious Dutch who wanted to run onto the tatami, he bowed deeply to Kaminaga, his opponent from just a moment ago, the Crown Prince and the Princess, the Queen of Holland, and left the hall with dignity. What I had just witnessed was nothing more or less than a sober, but oh-so eloquent manifestation of this spirit of the bushidō for which I had been for so long a tireless missionary. And I think that all those who had the chance to attend this scene had to find that there stood in front of them a proud judoka.

A few days after the Games, the new Olympic champion would touch the hearts of the Japanese public in accepting to participate in several "Japan versus the Rest of the World" tournaments held in four different cities – Fukuoka, Tenri, Nagoya and Sendai. His friend Bruno Carmeni, who had trained for three months in Japan with Geesink before the Olympic Games during which he competed in the lightweight division, accompanied him. The Italian later wrote: "Geesink accepted, even though he made enormous efforts at the Games, while the other medallists Nakatani, Okano, Inokuma and Kaminaga declined. Geesink was considered 'untouchable' and was totally respected."

Through his chivalrous, warrior-like attitude, Geesink had won the eternal respect of an entire people, whom he had nevertheless plunged into deep despair. Japan would never forget his elegance. Subsequently, each of his numerous trips to the Far East, the giant from Utrecht would always receive a welcome worthy of a head of state. Even during his last stay in Japan, well into his 70s, children born well after this page in Tokyo's history would recognise him in the street and bow to him in deference.

Judo's debt to Geesink

One year later, Geesink picked up a final world title at Rio de Janeiro in the new heavyweight category, which was being inaugurated. After this he bowed out with the status of a living legend. Cashing in on his notoriety, he segued from the judo halls to the silver screen, making some rather forgettable films and mediocre Dutch television shows. Then, in the 70s, Geesink wrestled professionally in Japan, before devoting most of his efforts to teaching and popularising judo – activities which would have no doubt pleased his master Michigami, whom he drifted apart from for years before reconnecting late in his life.

More than half a century after his Olympic masterpiece, and almost 10 years after his death, Geesink remains one of the most significant figures in the history of his sport. Judo arguably owes to him a large part of its current scope and universality. Taking to the tatami in Tokyo was only meant to be a one-off. The discipline had not even been considered as part of the Olympic program for Mexico City in 1968. But given the magnitude of the event of Geesink's victory, the IOC decided to reintegrate judo as an official sport for Munich in 1972.

On becoming the first non-Japanese 10th dan judoka in 1997, Geesink stressed his conviction that his victory in the Olympics did not just belong to him. "I believe," he said, "that the Japanese only really accepted my victory when they admitted that if all four Olympic titles at Tokyo had been won by their representatives, judo would not have remained an Olympic sport." And that, the global preservation of an entire sport, was probably Geesink's greatest triumph.

Written by Laurent Vergne, translated by Felix Lowe

Scan me

Related Topics

Share this article

Advertisement

Advertisement