The Essential Olympic Stories: Bob Beamon’s leap of the century

At the Mexico Olympics of 1968, Bob Beamon redefined the boundaries of the possible by shattering the long jump world record with his first jump in the final. The American’s leap of 8.90 metres pulverised the competition and was a staggering 55 centimetres better than the old benchmark. This almost immeasurable record would endure for over two decades.

Sponsored by

Bridgestone:focal(1265x722:1267x720)/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2023/08/24/3768965-76669228-2560-1440.png)

The Essential Olympic Stories: Bob Beamon’s leap of the century

Not many people make a true and lasting impression – and even fewer are remembered by posterity. Bob Beamon is among the yet more infinitesimal number of champions whose legacy to history is far greater. His success was not only beyond belief, it also questioned the very laws of gravity and logic.

His achievement was so indescribable that it inspired a new word in the English language. This adjective – Beamonesque – came into being more than half a century ago and relates to an athletic feat so dramatically superior to previous feats that it overwhelms the imagination. It is a term that has been rubber-stamped by the International Olympic Committee, yet one that is often used in sports jargon without a true appreciation of its etymology.

But anyone who witnessed Bob Beamon take flight on that stormy day on 18th October 1968 would be left in no doubt as to the true sense of the word. A few months before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon, Beamon took his own giant leap for mankind. Only he didn’t have a rocket – just two legs that could give any NASA engine a run for its money.

Beamon’s flight took place in Mexico City at an altitude considerably lower than the moon. But it was an altitude conducive for breaking records and changing the course of destiny, all the same. In the space of six short seconds and nineteen strides, the American took a stratospheric leap to legendary status. He did it his way – and unlike all others. Because Beamon’s rise to the top of his sport was so abrupt and yet so succinct that it remains, to this day, without comparison.

An eternal print in the sand

At the Mexico City Olympics, Beamon did not merely win the contest of a lifetime. Beamon above all established himself as an immeasurable legend in one jump – taking off, soaring through the sky, and coming to land with his feet practically in another century.

To this day, his 8.90 metres made that electrifying afternoon remains the second longest wind legal jump in history. Only Mike Powell, at the end of another intoxicating evening, has jumped further.

On 30th August 1991 at Tokyo, Powell and fellow American Carl Lewis played out a captivating duel in the sandpit. This was the same imperious Lewis who’d been chasing Beamon’s record for a decade. He had never been closer to it than the moment when Powell snatched it from under his nose. Lewis had been considered Beamon’s successor. Indeed, he’d even gone one centimetre further than the legendary landmark – only to see the jump discounted for being over the wind-legal limit. Then Powell, the unknown challenger, pulled the carpet from under Lewis’s feet with a leap that finally put Beamon’s in the shade by five centimetres.

To say that seeing Bob Beamon clinch gold in Mexico was as big a surprise as seeing Powell unseat Lewis and snatch a record that seemed unattainable to any jumper other than “King Carl” would be a lie. Because, despite the stellar line-up at Mexico – which included the two co-world record holders, Ralph Boston and Igor Ter-Ovanesyan (8.35m), and the two previous Olympic gold medallists in Lynn Davies and Boston – the young Beamon, just 22 years old, looked like the real favourite.

His results in 1968 justified this – Beamon having won 22 of the 23 meets he had competed in that year. The prospect of Beamon beating the world record was not so far-fetched, either: since the start of the 60s two athletes had set eight new records, adding 19cm to the record over eight years. What’s more, the American tyro had recently posted the longest indoor jump in history (8.30m) while, outdoors, he had cleared a career-best 8.33m at the AAU championships in Sacramento in June. Beamon had even landed 8.39m at the Olympic Trials at Echo Summit in September – albeit well over the wind-legal limit of 2.0 metres per second.

“If Beamon manages a perfect take-off from the board in the final, not only will nobody be able to come close, but he seems capable of breaking the 8.60-metres barrier provided luck is on his side.” This was the bold prediction of Robert Parienté in L’Equipe. But if he was right in one regard – no one, indeed, did come remotely close – he also grossly underestimated Beamon’s performance.

Beamon’s rise sandwiched by war and revolution

Robert Beamon was born in 1946 after the end of World War II. He made his mark in 1968, a heroic, dramatic and, undoubtedly, the most fascinating year of the second half of the 20th century. Twelve months of varying revolutions held a gigantic middle finger to the established order, deployed in the twilight of a contradictory decade, where great advances were made with the foot still firmly on the brake.

Beamon had raw talent rarely seen in a lifetime. The kid was taller and slenderer than his rivals – 1.91m and 68kg as an adult – with springs in his calves and a golden touch. Long before he leapt to athletics immortality, he was a local star on the basketball courts of the Big Apple. It gives you an idea of his ability when you consider that Beamon was drafted to the NBA in 1969, in the 15th round, by the Phoenix Suns.

Already an Olympic champion at this point, his shift from the sandpit to the parquet floor was far from spectacular – although he always claimed that athletics wasn’t enough to put food even on superman’s table. Lured by a salary of $250,000, Beamon never made an appearance in the NBA. But he always preferred shooting hoops to jumping, once claiming that he “could have jumped 35 feet (10.67m) if I had practiced track as much as I have basketball”.

Gangs of New York

Beamon’s youth is the story of an unlucky seed growing up in the wrong soil. Young Bob never knew his mother because she died from tuberculosis long before he was old enough to remember her. His father, meanwhile, was a regular behind bars and was locked up in the notorious Sing Sing prison when his mother fell pregnant – something which understandably became something of a sore point between his parents.

“My mother didn’t take me home because she was too ill to care for me,” Beamon laments in his biography, The Man Who Could Fly.

In South Jamaica, the district of Queens where he grew up, Beamon lived either in a boarding house, with his grandmother or, despite his initial reluctance, with the man he believed to be his natural father. Between two periods in jail, his stepfather ended up accepting the kid and took care of him as best he could – which was not exactly saying much.

At this point in his life, Beamon would later admit that his prospects were “very limited”. He was largely left to fend for himself in an area where feeling lonely was a sign of weakness. In this hostile environment, playing basketball offered him some relief. If he wasn’t jumping far just yet, he was already jumping high. And the bigger kids loved it: Beamon regularly found himself picked to play in their teams, which gave him a sense of belonging that he lacked elsewhere in life.

“Basketball is big stuff in New York,” he would later explain. “If you’re good at it, everybody respects you. Nobody would want to ruin your shooting eye or your shooting arm.”

To cover his back, Beamon fell in with a bad crowd. “I joined a gang. We called ourselves The Frenchmen,” he says in his book.

There were about fifteen to twenty of us, mostly from South Jamaica Housing Projects and mostly between the ages of twelve and fifteen.

He smoked, he drank wine – perhaps the origin behind the name of his gang? – and even sold drugs as a side hustle.

School was, unsurprisingly, not high on his list of priorities. And yet it was school which would get Beamon back on the right track – along with a little help from his grandmother, too. When Bob found himself kicked out of college, Bessie took matters into her own hands. She took her grandson in and then sent him to a “600” school in Manhattan – a special institution for troubled children.

Victory on Randalls Island

Removed from his natural habitat, Beamon gradually got back on his feet. Still extremely talented with a ball in his hand, he made one of his teachers remark: “You know, Beamon, if I could play basketball like you, I wouldn’t be doing it in a 600 school…” His grandmother also forked out on some decent clothes for him – no more rags or oversized garments. The result was that everyone’s perception of Beamon changed almost overnight.

At school, Beamon tried his hand at athletics and he quickly got the bug. During his second year at the faculty, he took part in a meeting and won the 50m, 100m and 200m races, as well as the long jump (of course). In 1962, aged 16, he saw a poster advertising the “Junior Olympics” – a local competition for youngsters. It was held on Randalls Island – on the East River between Manhattan and Queens, an hour from his home. He had an overwhelming urge to seize his chance and compete. Although, as he couldn’t afford spikes, he had to borrow a pair from another kid when he turned up just 15 minutes before his event.

“It was a clear day, not a cloud in the sky,” Beamon recalls. “It was so blue and I felt free, so unrestricted. When my name was called, I didn’t even think about anything. I walked to the runway, composed myself for a moment, and then sprinted down the runway and took off at the board. When I landed, I had broken the Junior Olympics long jump record. People probably wondered who I was and where I came from as I stood at the victory podium with the gold medal dangling from my neck. I couldn’t have answered that – I didn’t know myself.”

The next day, his name appeared for the first time in the local newspaper, the Daily Mirror: “Bob Beamon jumped 7.34 metres”. An athlete and an ambition had been born. His stepfather could not pass up this opportunity. He went to South Jamaica High School with a copy of the article in his hand and showed it to Larry Ellis, a renowned athletics coach, and asked him to take Bob under his wing. Ellis accepted. But there was a caveat: Jamaica High School was a traditional school – one transgression and Beamon would be thrown out.

At this point, Beamon was still playing a lot of basketball. But he was clearly making strides in his new discipline: in the long jump he was the 10th best high school student in the country in 1964. A year later, he rose to second place in the national rankings and was also a triple jump phenomenon. His progression was rapid. As he would later say, “raw and undisciplined talent” gradually polishes itself; the cream was rising to the top.

Marriage and complicated studies

Beamon’s life suddenly sped out of control. Before even heading to college, where a scholarship awaited him, he married the young woman who said she was carrying his child. Not only did the customs of the time call for him to do the honourable thing, but – and probably more importantly – his grandmother insisted.

Nine months later, when studying and training at North Carolina A&T, it struck him that the baby had still not showed up. It was only then that Melvina, his wife, told him that she’d had a miscarriage. To say that he felt betrayed would be an understatement.

Beamon returned to New York at the end of 1966. His grandmother had begged him to drop out of college to support Melvina, but Larry Ellis did not want the talent of his 20-year-old prodigy to slip through his fingers because of such material considerations. He put him in touch with Wayne Vandenburg, a coach at the University of Texas and El Paso. Vandenburg wanted to bring him onto the campus but Beamon was still unsure.

One day soon, Bob Beamon is going to make a jump that you won’t believe and I won’t believe.

Right from the start of their relationship, Vandenburg was convinced of his young jumper’s greatness. But life in El Paso was, to say the least, a challenge for the New Yorker. At UTEP, there were 10,000 students and only 250 of them were black (most of whom were athletes). As tensions rose in Detroit during the long, hot summer of 1967, Beamon’s political consciousness grew while attending this predominantly white institution.

Beamon may have had his eyes set on Mexico but he was not wearing blinkers, either. He realised that America was being pulled apart on the issue of ethnic minorities. The United States, under the presidency of Lyndon Johnson, legislated and legally advanced the cause of black people with the Civil Rights Act. But there was a vast gulf between the letter and the spirit of the law.

Beamon vs the Mormons

The man who would jump longer than anyone else in history was a child of segregation – the very same that Martin Luther King had fought against for over a decade. King would lose his life fighting this cause, assassinated by James Earl Ray in front of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on 4th April 1968. It was within this context and with infinite sadness that Bob Beamon told himself that it was time to take a stance and bring his fist down hard on the table.

Over the Easter weekend that year, UTEP took on Brigham Young University in a meet. BYU was a Mormon institution. It was 8th April 1968, the day before King’s funeral, when nine members of the UTEP athletics team, including Beamon, called a meeting with coach Vandenburg, telling him they were going to boycott the meet. Their reason was quite simple: the Book of Mormon.

Beamon and his mates knew full well that they were playing with fire – but they stood their ground and paid dearly for their actions. “I lost my scholarship,” Beamon recalls in his book, “but, damn it, I wasn’t going to lose my dream. I continued training for Mexico City. Being an Olympian was not going to be a dream deferred. Not for me.”

The death of Martin Luther King, followed by that of Bobby Kennedy two months later, had triggered a sense of urgency in him. “Life is too short and too precious to mess around with,” he later wrote. But without a team or any funding, Beamon was forced to take on Olympian Ralph Boston as his unofficial coach in the run-up to the Games. Despite all this drama, Beamon remained focused.

El Paso and Mexico City may have been separated by a border, but ideas still flowed freely across the frontier. The capital city of Mexico, which was hosting the Games of the XIX Olympiad of the modern era, was not spared the ills of the time. It was indeed just 10 days after the Tlatelolco massacre, which claimed the lives of over 300 unarmed demonstrators, largely students, that the 1968 Olympics opened its doors. The pot was bubbling away and it wouldn’t take much for the lid to pop.

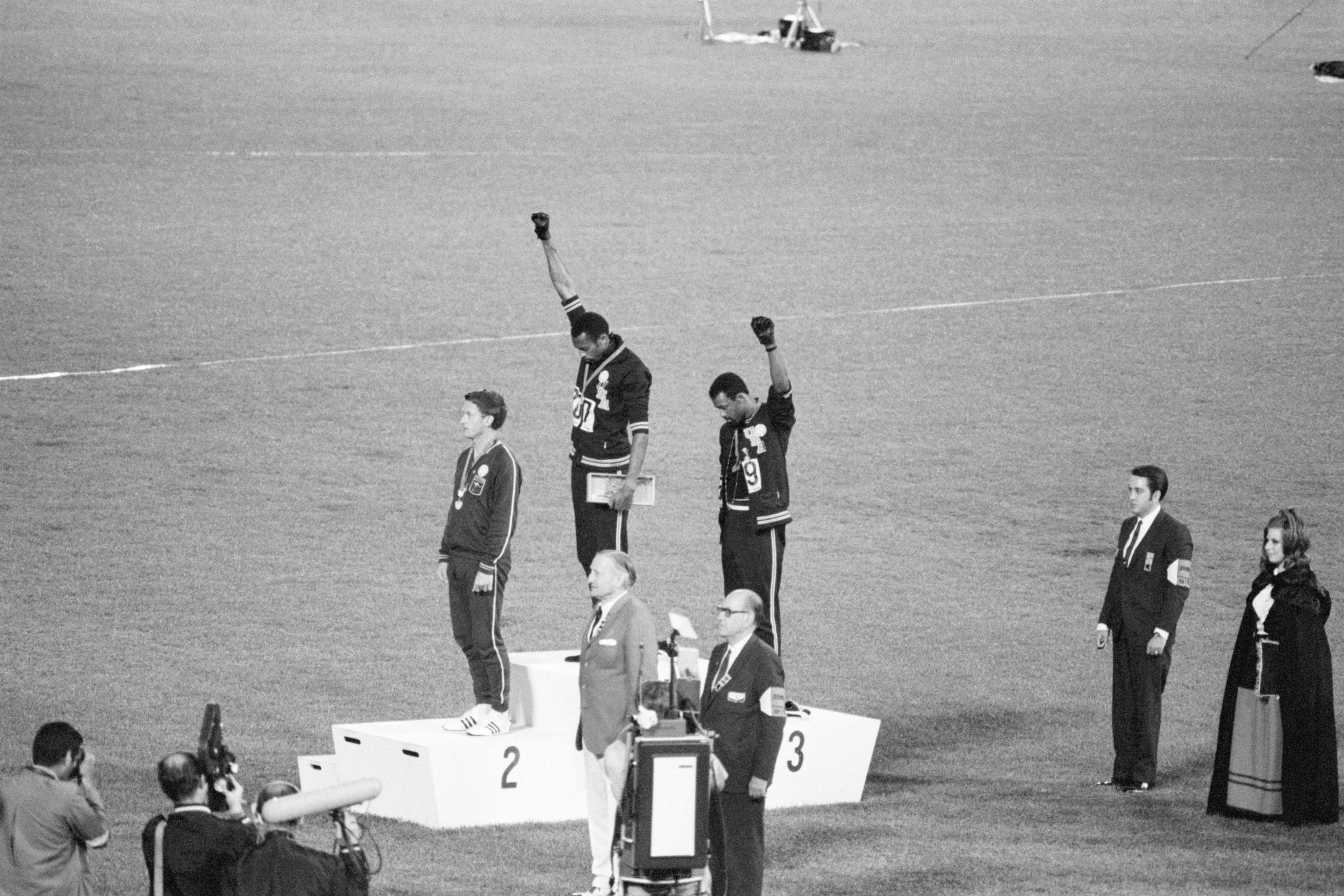

On 16th October 1968, four days after the opening ceremony, the Games were already caught up in the crossfire of social unrest. On the 200m podium, Tommie Smith and John Carlos bowed their heads and raised their gloved fists to the sky. Two days later, on the morning of the long jump final, both men were asked to pack their bags and leave the Olympic village.

Flirting with elimination in the heats

Beamon was still there – but by the skin of his teeth. The day before, the young jumper almost fell at the first hurdle: two foul jumps in the heats meant Beamon found himself staring down the barrel of a gun and on the brink of elimination. Boston, his mentor who took gold in Rome and silver four years later at Tokyo, took Beamon aside and helped him relax. At the last roll of the dice, Beamon pulled it out of the bag. Like Jesse Owens, in Berlin, he had flirted with disaster but his third jump, measured at 8.19 metres, was enough to put him in the final – and showed what he was capable of.

Beamon’s activities on the night before the final have been the subject of much speculation. If the stories have varied over the years, it is at least certain that he did not exactly follow the copybook for high athletic performance. In his biography, Beamon says that he spent the evening making love to his childhood sweetheart, Gloria, the girl he would have married had his hand not been forced otherwise.

But on other occasions, Beamon also has admitted to being antagonised by the expulsion of his Team USA buddies, Smith and Carlos. This forced him to go and blow off some steam. “Everything was wrong. So I went into town and had a shot of tequila. Man, did I feel loose. I got a good sleep.”

In any case, the next day, at 3:46pm, Beamon found himself standing on the runway with the 254 bib on his back. It was 23.5 degrees in the heart of the Olympic stadium with a humidity of 42%. Beamon was the fourth jumper in the 17-competitor final. The conditions were testing – the first three jumps were fouls – and the sky was visibly darkening as a thunderstorm approached.

“We wondered if we were going to be able to jump,” the Frenchman Jack Pani recalled a few years ago in the newspaper Ouest France, looking back at his seventh place in the final. “The rain was coming. There were terrible gusts of wind. And because it was blowing from behind, we had no idea what the effect it would have on the runway.” A storm was indeed brewing. But before the heavens opened from above, there was a clap of thunder down below.

As Beamon stood 40 metres away from the sandpit it would be wrong to say that the public only had eyes for him. For taking place at the very same time was the final of the 400m, which would give birth to a new world record, the first under 44 seconds. This race held the attention of the spectators, most of whom probably felt that the long jump final – which, after all, had only just started – would still be going on way after the American Lee Evans romped home in a time of 43”86. Big mistake.

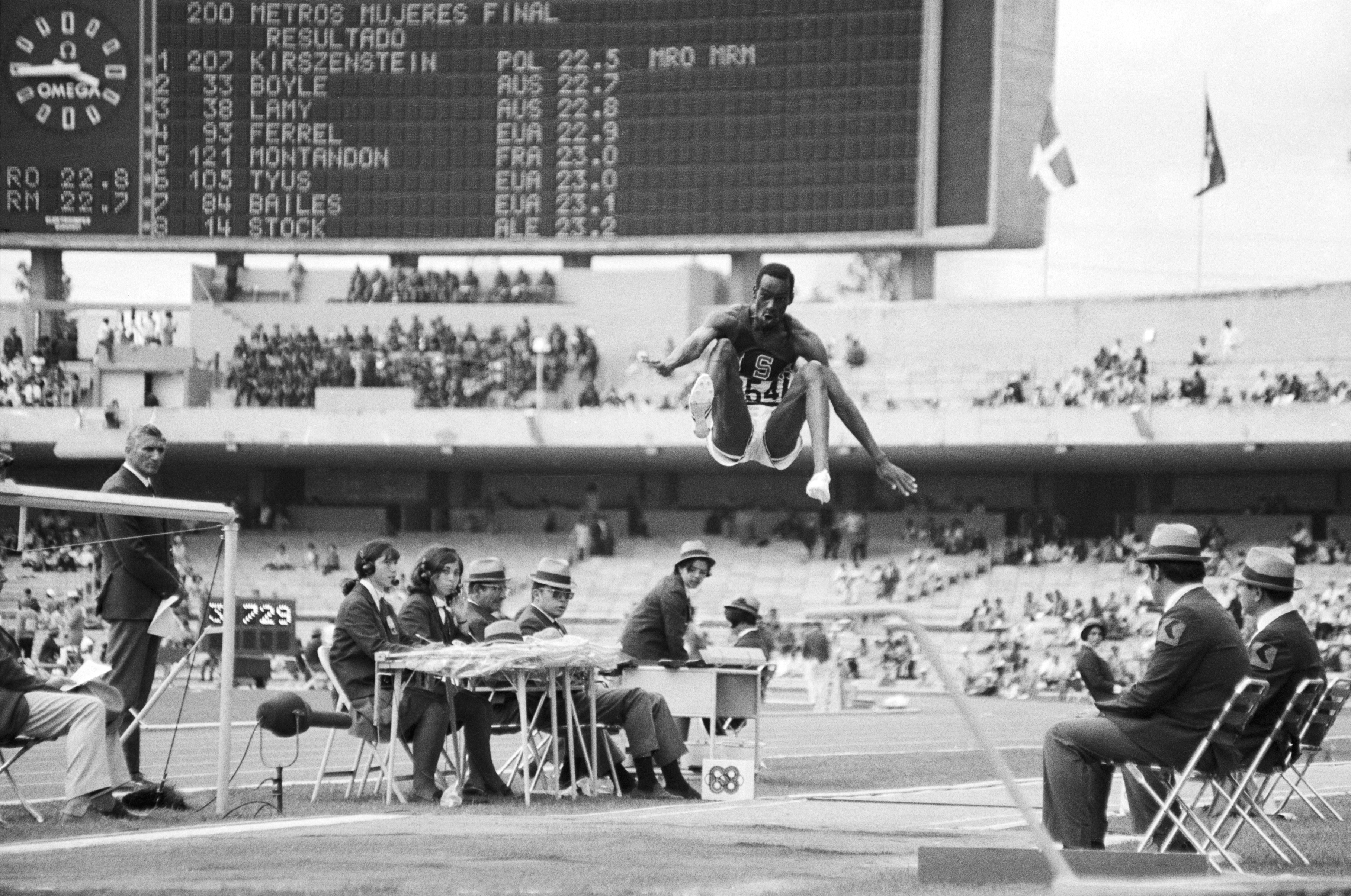

Just seconds later, after he lolloped up the runway, Beamon and his lithe limbs took off. His rangy torso soared through the air, defying the forces of gravity as they seemed to hover six feet (183cm) above the ground. After what seemed like an eternity – Beamon said he felt like he was suspended for an hour before finally landing – his body came to earth in rather unconventional means. Let’s just say that there was room for improvement in that department – but, then again, no one is perfect.

“I landed with such impact that I continued to jump like a kangaroo hopping out of the sandpit. I was not very happy with my landing. Hell, how could I have landed on my butt and not on my feet! ‘That will cost me inches,’ I thought. ‘Damn, I messed up – I really did land on my butt – I’ve lost at least a foot,’ I thought.”

While the landing was not without fault, what preceded it was successful beyond all realms of the imagination. Sitting on a bench next to the runway, Boston took stock of the exceptional sight that he had just witnessed. Turning to the reigning Olympic champion, he said: “That’s over 28 feet!” To which Lynn Davies replied, incredulously: “With his first jump – no, it can’t be?”

The man whose world record was about to tumble had yet to take off his tracksuit but already he knew that it was now a battle for the silver medal: his compatriot had jumped so far that the contest was effectively over.

The leap of a century literally off the scale

No sooner had Beamon returned to his feet than one of the judges entered the sandpit to calculate the score. First, the white flag went up: there was no infringement on the board. The anemometer then indicated… two metres of favourable wind per second, the top of the authorised limit. This meant the jump would stand and could be measured – provided the technology allowed it to be.

Boston was right: Bob Beamon had jumped over 28 feet. Well over. Put simply, he’d leapt beyond what was both imaginable and technically expected back then. The Mexico City Games were those which oversaw a switch to electronic scoring across the board. The competition was measured by an optical device which ran along a rail. The scorer extended the device as far as possible – but there was a problem. The officials had capped the distance at 8.60 metres. Beamon’s jump was so extraordinary it was also immeasurable.

As he hopped away, jauntily swinging his hips and arms, relieved at having not overshot the board following the drama of the chaotic heats, Beamon left the judges to their improbable conundrum. Not only had he jumped the farthest, he also somehow managed to stop time that day for what seemed like an age. In truth, it was really no more than the jump deserved. After 15 minutes, it was decided that the IAAF officials would have to resort to tried and tested methods and measure the jump manually. The leap of the century would require a measuring tape.

When the announcer finally called out the distance for the jump – 8.90 metres – Beamon, unfamiliar with metric measurements, still did not realise what he had just done. He knew he had become the new world record holder, but he had no idea by how much. Until Boston did the maths for him and made the conversion: 29 feet and 2.5 inches. In other words, 21 and three-quarter inches longer than had ever been jumped before.

‘You have destroyed this event’

When Beamon finally came to realise the enormity of his achievement, his legs gave way and he fell to the ground. He suffered a brief cataplexy attack brought on by the emotional shock. His head in his hands and needing Boston to hold him up, the new world record holder had been reminded of his own immortality just minutes after making history.

“Compared to that jump, we seemed like kids,” the Soviet athlete Igor Ter-Ovanesyan said, almost exactly one year after he had set the previous joint world record in the very same stadium. Davies, the defending champion, approached his successor and told him: “You have destroyed the event”.

“That may be but that first jump almost killed me, too,” Beamon allegedly replied, once he had regained his senses.

Symbolically, the storm clouds that had loomed over Mexico City suddenly poured down on the Olympic stadium and washed away any remote chance of any kind of reversal. Gold was already a foregone conclusion, but Beamon jumped again – a modest 8:04 metres. Then, he put away his spikes. The conditions had deteriorated further, and a wet track and swirling wind ended any chances of somebody matching Beamon’s heroics.

Before stepping onto the podium, Beamon rolled up his tracksuit trousers to his calves, revealing the black socks he wore in solidarity with Smith and Carlos. On the top step, he raised his fist as a rallying cause of black Americans. The new king was then overcome by a fleeting yet gloomy thought: “What now?” The Olympic champion and world record holder was suddenly dizzy with the vertigo of his achievement. He did not know at the time, but he could probably sense it inside: his single moment of greatness was already behind him.

The man who made the leap of the century to shatter the world record by 55 centimetres never came close to matching his Mexican landmark. Indeed, Beamon would never jump further than 8.16m after the day he brought time to a standstill. Injuries and the pressing need to make money would soon submerge Beamon, a man drowned out by everything going on around him.

“I reached a height when I had just turned 22 years old,” he later said. “I was a student in college and married and trying to compete as an international-class athlete. And those were the late ‘60s, with upheavals with blacks and whites, the women’s movement, assassinations, the middle class discovering drugs. It was a strange time. And I got kind of lost in it.”

‘Some viewed my performance as racial contempt’

If Beamon was in shock, so too was the rest of the world. And perhaps unsurprisingly, it did not take long for people to start seeking answers. Was it really possible to beat a world record by such a margin? The wind was blowing hard that day – but was it really only two-metres per second?

He took these questions in his stride. Except when some were loaded by the issue of race. “There were scientists who analysed my jump using the laws of physics, discussing velocity, trajectory and aerodynamics, among other things,” he explains in his book.

“Then there were others who analysed my performance and my life based on their personal slant of racial disdain. They played the race card when they said that I had jumped that far because I was black. After all, they said, blacks have longer legs, thicker ankles and that our muscular make up is different. That’s why they said blacks made good slaves: strong bodies with no brains. They called me superhuman and referred to me as a jumping machine. But, thank God, everyone did not and does not think like that.”

Mexico 1968 was an exceptional Olympics. It is no coincidence that 14 world records and 12 Olympic records fell in athletics across 36 track and field events. In the triple jump, the world benchmark was broken on five separate occasions in a competition that would go down in the history books. Jim Hines was the first to break the 10-second barrier in the 100m with a winning time of 9”95.

Sprinters and jumpers took advantage of the favourable meteorological conditions associated with the altitude of Mexico City. At 2,200 metres above sea level, the air resistance is lower. Add to that the technical developments, embodied by the introduction of tartan running tracks, and you had an explosive and performance-friendly cocktail. In the case of Beamon, it should be added that he had the good sense of pulling off a near-perfect jump just ahead of a threatening thunderstorm which had considerably reduced the air pressure.

“There is no answer for the performance,” Beamon told the New York Times in 1984.

But everything was just perfect for it: the runway, my take-off – I went six feet in the air when usually I’d go about five – and my concentration was perfect. It never happened quite that way before. I blocked out everything in the world, except my focus on the jump.

More than 15 years later, during the Los Angeles Games, when Carl Lewis won the gold medal with a jump that was still 34cm shorter than the world record, Beamon had the confidence to say: “All I know is, I don’t see anybody else doing it. Not then and not ever. There have been meets in Mexico City since then, and at other places with high altitude. And the record is still in the books.”

As it happened, seven years later, at the 1991 World Championships in Tokyo, Mike Powell broke the 23-year-long record by 5cm at the end of a thrilling duel with Lewis. Beamon’s record may have been erased from the books, but the memories won’t follow. Until proven otherwise, no one has ever talked about a “Powellesque” performance.

Translated by Felix Lowe

Scan me

Related Topics

Share this article

Advertisement

Advertisement