Blood On The Carpet: How Higgins and Davis made modern snooker

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2015/04/22/1462335-31243733-310-310.jpg)

Updated 25/07/2020 at 13:27 GMT

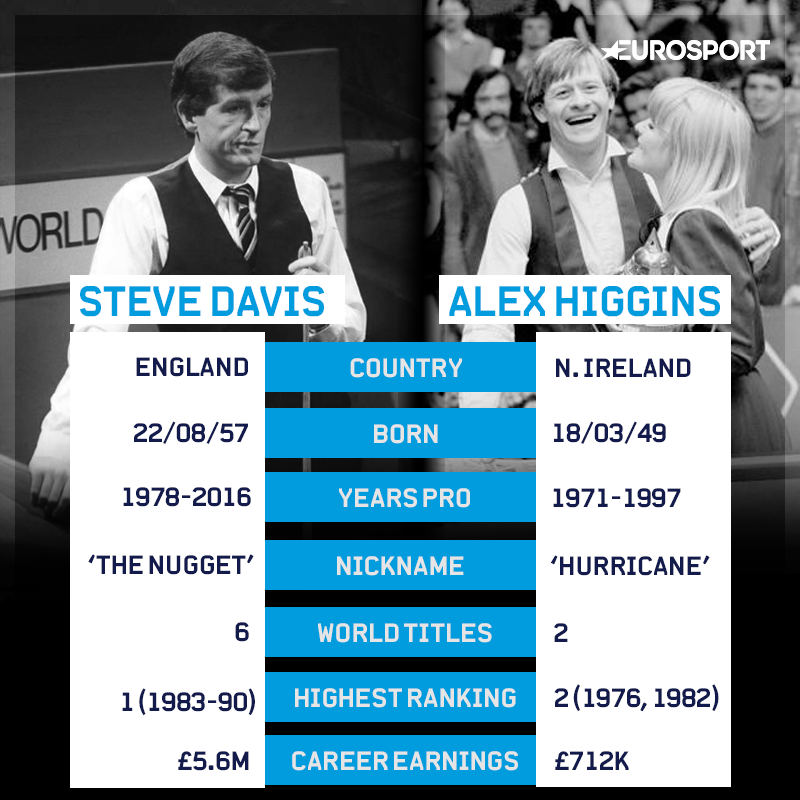

History will judge Alex Higgins and Steve Davis not merely as snooker's most memorable enemies, but as the founding fathers of the modern televised game. In particular, the antics of Higgins gave the sport serious heft at a time when risk-taking was avoided at the outset of professionalism.

Steve Davis and Alex Higgins - Phil Galloway for Eurosport

Image credit: Eurosport

1. Jewels In The Crown

Out of the British Raj, it became all the rage. The enlivening but enervating sport of snooker was invented by British army officers in colonial India in the 1870s, but officially colonised by British television coverage in the 1970s and 1980s.

Steve Davis and Alex Higgins, multiple world champions and genuine giants of their darkened domain, remain jewels in the crown far away from the game’s origins, figures of snooker folklore who managed to make their game a matter of national debate rather than merely a trivial pastime to while away the hours between tiffin and teatime drinks. Drinks that latterly became gallons of beer and vodka swallowed by the doomed, chain-smoking, flawed, but utterly absorbing Higgins on live television.

If the sport of snooker was spawned in the officers’ mess, it was given fresh meaning by the walking mess that was 'The Hurricane’. Nobody in professional sport in any walk of life has been bestowed a more glorious nickname than Higgins, a flamboyant, belligerent Belfast boy who played snooker as fast as a hurricane and lived his life in one.

A rancorous rivalry that transcends snooker was made in a green baize Babylon: Davis, a clean-living, compulsive winner from Romford in Essex, snooker's technically and mentally unshakeable champion against the twitching, animated, epic sporting hellraiser Higgins, a fabulous, fidgeting talent blighted by the inner demons of depression on his way to drinking, smoking and snorting his way into an early grave at the age of 61 in 2010.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2017/04/13/2062525-43245987-2560-1440.jpg)

Alex Higgins

Image credit: Imago

He was finally overthrown by the percentage game he detested after a tragic battle with lung cancer. It was malnourishment that was said to have buried him after he was rendered a marginalised skeletal figure slurping Guinness without any teeth.

In the death throes of his life, he was left a shell of his rampaging glory days, watching Cash in the Attic in Belfast sheltered housing after hemorrhaging an estimated £3m-£4m in what was described by one newspaper as the longest suicide in sporting history. As is said, you don’t tell the drink, eventually it tells you. Yet the gilded memories never die. The ghost of Higgins continues to stalk the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield, an outpost that has become a unique fundament due to such storied icons.

It is a poignant time to reflect and remember the origins of the sport in its modern televised form; fighting out of working men’s clubs, heavy industry and dowdy billiards halls to an event today witnessed by over 300 million viewers in over 100 countries.

2. Working Class Heroes

Under the unrelenting glare of TV cameras, snooker has yet to witness a fiercer rivalry than that of Davis and Higgins in the 1980s - both working class heroes but of varying degrees of class - which not only sated their own competitive instincts, but also unwittingly brought a soap opera into living rooms up and down the UK that had more dramatic effect than Dirty Den.

It aroused a widespread interest in the sport. It gifted snooker players the type of profiles enjoyed by Premier League footballers. Two men led snooker into a brave new world with Higgins manning the ship with a cue in one hand, and a packet of woodbine and a large vodka in the other. With the advent of colour TVs seemingly built to broadcast snooker in the 1970s, there were other jobbing performers, but none more riveting than the main protagonists.

Both true artisans in styles as different as the black and white balls. Davis, studious, concise and measured in moving gingerly, assembling his opus; Higgins, shifting as fast as he sniffed with a waif-like boyish charm; both should be recognised as unlikely founding fathers of the modern game that we witness most visibly on a yearly basis in the 17-day bow-tied torture chamber of the World Championship.

In the 1980s when there were only four channels, everybody thought they knew you. It was like you were in Eastenders.

It is not difficult to see why snooker in the 1980s continues to be perceived as the golden era: there were only three, then later four, TV channels embracing a captive audience. The BBC and ITV were attracted to the sport due to the cheap cost of coverage. Higgins provided noise, frisson and large dollops of outlandish pots for free.

"Without the flamboyancy of Alex Higgins, snooker would not be where it is today," the six-times World Championship runner-up Jimmy 'Whirlwind' White, a figure who helped carry the coffin at Higgins' funeral, tells Eurosport. "In the 1980s when there were only four channels, everybody thought they knew you. It was like you were in Eastenders. For me, Alex Higgins made the game of snooker. I think most professionals like Mark Selby and Ronnie O'Sullivan would agree with that."

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2015/04/22/1462430-31245617-2560-1440.jpg)

Jimmy White and Alex Higgins with Rolling Stone Ronnie Wood.

Image credit: Eurosport

To put snooker’s popularity into some kind of perspective, when Davis won the last three of his six World Championships in 1987, 1988 and 1989, he snagged more money in those three years than golf’s Open champion - the £105,000 he enjoyed in 1989 dwarfed Mark Calcavecchia's £80k for lifting the Claret Jug. When Selby earned £350,000 for lifting a second world title in 2016, Henrik Stenson's Troon tapestry the same year was worth £1.175m. The sports have gone their separate ways financially.

"Snooker players are no longer noticed like they were in the 80s when they walked down a street,” conceded Davis in an interview with me back in 2009. “There are more TV channels, people have other things to do, but the viewing figures remain very healthy."

But not as healthy, or perhaps unhealthy, as when Higgins was on the loose. Ironically, snooker has never been performed at a higher level than over the past two decades, but attention spans have dwindled. Yet it was once a very serious affair for the Great British public. A matter of life or death? More than that for some.

Davis was infamously booed into arenas up and down the land after spending more time at the table than Louis XIV of France. He didn't mind. He was an immaculate teetotal snooker addict who became the first professional hell-bent on practice, winning and maximising his talent in the pursuit of perfection. His father Bill reared him on the book How I Play Snooker by Joe Davis, titan of snooker during two world wars. The younger Davis never complained about the dubious pleasures of practice.

Higgins by cutting contrast was emotional and mixed up; a geezer whose brilliance on the table was outdone by the torrents that raged in his private life where gambling, drugs, booze and random explosions of violent behaviour saw him become a figure of fascination the public could relate to.

I will have you shot

Long before the rise of digital and social media, you tended to judge your heroes by how you viewed them on the little box in your living room. Higgins consisted of as many personalities as the shots he could pull off. It made him an almost mythical force of nature, but the dark side of 'The Hurricane' was never far from spiralling out of control. He infamously assaulted match officials at will, headbutting the tournament director at the 1986 UK Championship after refusing a drugs test. He was fined £12,000 and banned for five tournaments, but was remarkably allowed to continue playing at the event despite the cops being called. Then came the 1990 World Championship where he punched an official in the stomach.

His win over a young future world champion Stephen Hendry at the 1989 Irish Masters was his last nod to the entire purpose of playing the game before his sense of self-harm finally began to eviscerate a once burgeoning career. Higgins, a Protestant from the Sandy Row area of Belfast, was banned for a season after threatening to have fellow player Dennis Taylor, a Catholic from the other side of the community, shot during a team event representing Ireland in 1990. "I come from Shankhill and you come from Coalisland," he said, "and the next time you are in Northern Ireland I will have you shot."

Higgins had caustic relationships with various people, including Taylor and Canada's 1980 world champion Cliff Thorburn, who floored him one night in a bar after Higgins had called him a "Canadian c***". A vexed Higgins signed the death warrant on his career at the highest level after the Taylor incident as he faded into relative obscurity at the outset of the 90s, still railing against officialdom during his last match at the Crucible, a 10-6 loss to Ken Doherty in 1994. Time out was not time well spent as he could not find the elixir in the bottom of a pint glass to catapult himself back into the reckoning.

If snooker was a relic of the Raj, Higgins was a relic of the rage. Yet the public loved Alex simply for being Alex.

3. Mayhem In The Matchroom

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2017/04/13/2062372-43242927-2560-1440.jpg)

Barry Hearn celebrates with Steve Davis after he won the 1988 World Championship

Image credit: Imago

Barry Hearn has been chairman of World Snooker since 2010, but remains most renowned as manager of the all-conquering Davis during his halcyon days.

There is a memorable scene at the 1981 World Championship after the 23-year-old Davis dismantles Doug Mountjoy for the first of his six world titles. Hearn bounds down to almost ragdoll Davis with as much glee as a punter with a few bob on Bob Champion and Aldaniti to win the Grand National in the same year. It must be said, Hearn, whose Matchroom Sport business promotes 11 sports including snooker and darts with a turnover of £70m, is a fabulous raconteur in recalling the days of his life.

“Steve’s idea of a risqué night was whether to drink two glasses of milk before bed where Alex would want to drink the place dry and have a fight with someone,” Hearn tells Eurosport. "Most of my job early doors was making sure Alex never got anywhere near Steve because Alex was very unpredictable. Steve was very uncomfortable around him. I had to have a word with the organisers when we were up in Scotland to tell them Alex wasn’t allowed within six feet of Davis.

“In Romford, we had a room there which we opened up in about in 1974/75 which we called the matchroom. The matchroom was outside the main billiards hall. We put in a Riley Oak Imperial table, the best in my opinion, and benches to seat about 300 people. There were no windows, or fire exits. There was one tiny door to get in, and one tiny door to get out. It would fail every type of planning application these days. There was no air conditioning so everybody smoked, and you could hardly see across the room. It was like a Bangkok kick boxing venue. It was mayhem, but the people were daft about snooker.

“I used that room to encourage Steve by bringing down all the greats at the time: world champions Ray Reardon, John Spencer, Cliff Thorburn and of course Alex Higgins, the biggest draw of the lot. Davis became almost unbeatable in the matchroom. I used to gamble a lot when I was younger. Me and Davis came from council houses, and didn’t have any money. I used to pay Davis £25 a night for these challenges, but said I would give him a bonus if I won money from betting on him, and Davis always won at Romford.

It ended up with me and him having a row, and I had him up against a wall. It was chaos because Alex would have a fight with anyone

"They’d have no respect for the opponent, they’d be shouting miss and jeering, but that was the working class environment. Alex would walk in, and the first question he'd ask would be: what odds am I tonight? It started by Alex giving Davis 14 points of a start because he had never heard of Steve Davis. After two or three games of Alex losing his money, it became an even match and eventually you could get decent odds on Alex.

“The highlight of all those matches was the last one played over four days and nights, best-of-65 frames. Until this day, those lucky enough to be there will tell you they have never seen snooker like it. It wasn’t how many 100 breaks there were, it was how many frames there were without a 100 break. The table was quite tight which made it even more impressive. Davis would hit a 136, Alex would come back with 112. And so on. Alex was on £500 for that exhibition, and had another £2,500 of cash in his pocket. Alex would put the whole lot on himself playing for £3,000. Most of the time, I would have to spot him £50 for his bus fare home, but you were okay with it because of the entertainment he brought to the crowd.

“At the end of the penultimate session, in the race to 33, Davis was 31-20 up. The crowd had been giving him stick, and Alex was on a short fuse. He turned and said: 'You bunch of w*****s, that’s the f*****g last you see of me. And if you bought a ticket for tonight, tough s**t.' He stormed out. We went downstairs where Alex was having a drink. It ended up with me and him having a row, and I had him up against a wall. It was chaos because Alex would have a fight with anyone. I thought: 'We’ll never see him again.'

“Two hours later, he turned up bang on time. ‘Hi Barry, everything okay.’ He was Jekyll and Hyde. 'I’m going to steamroller this ginger c***,' he said. He couldn’t resist the chance to entertain a crowd. Taking away his ability to entertain the crowd was the worst thing you could have done to him. He would go for flash shots because he was a crowd pleaser. If Alex was on a train, and you saw him walking down the aisle, you’d hide behind your newspaper because of the thought of sitting next to a madman for three or four hours. If you were out there watching snooker, you’d bite your arm off to watch him because he did things nobody else could do. Davis respected him for that, but realised in longer matches he was very beatable.

“Of course, for Steve when he won his first major title it was written in the stars that he was going to beat Alex in the 1980 UK Championship final, and that was the one that really triggered his explosion. The victories were always sweeter when they were against each other. Of course, it was uncomfortable to be in their presence together, but it sold tickets: 3,500 people turned up at the Kelvin Hall in Glasgow to watch them. One of the biggest crowds ever to watch snooker because it was Davis v Higgins, it was the ultimate game of snooker. It remains the ultimate game of snooker."

4. 'Some Kind Of Magic'

Higgins won two world titles, against John Spencer in 1972 and Ray Reardon in 1982, but the second was the solitary world trophy he carried off at the Crucible. In the semi-finals against White, he trailed 15-14 and 59-0 when he came to the table. On the cusp of defeat, he produced a series of unbelievable pots despite appearing to have as much control of the white ball as a drunk. Which he could have been.

The clearance of 69 on his way to a 16-15 win over White is widely regarded as one of the finest, a totem of the times, at the Crucible before he usurped Reardon 18-15 in the final. There is a pot on the blue to a baulk bag when he has made only 13 which is particularly fearsome. In days of heavier balls and slower clothes, Higgins shaped the table against the odds with more bottle than a glassblower.

"It was a mental break, it was phenomenal," said White. "I didn't think he would clear up, no. There were about four shots he played that were amazing. His name was on the trophy that year. Did it cost me the World Championship? At that time I didn't care if I won or lost because I was having such fun. In 1979 and 1980, I went to Australia to play in the amateur World Championship which cost me two years of experience at the Crucible. Who knows? Maybe it was meant to be because I'm still playing now."

Joe Johnson, 1986 world champion and Eurosport analyst, agrees with White about the scale, class and audacity of the contribution.

“That break was some kind of magic,” said Johnson, who beat Davis 18-12 to win the 1986 world title as a 150-1 outsider. “I played Alex Higgins many, many times. We toured the Middle East together, and I loved him as a guy. He could be quite eccentric: one minute you knew where you were with him, the next he was a different person completely. But that is the enigma of Alex Higgins. I loved him, and I thought his snooker was unbelievable.”

5. Inspiring Ronnie O'Sullivan

There have been three men to enjoy the debatable moniker of the ‘People’s Champion’ in snooker: Higgins, White and Ronnie O’Sullivan. What does such a term mean? From what we can detect, it means you are popular because you are more interested in entertaining than winning. You are a man of the people because you give the people what they want.

Higgins and White, who won the world doubles title together in 1984, were have-a-go heroes, and crowd pleasers who loved a slice of life away from the machinations of the sport, but White is best remembered for losing six world finals, one to Steve Davis in 1984, one to John Parrott in 1991 and another four to Stephen Hendry in 1990, 1992, 1993 and 1994.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2010/08/02/631075-21957458-2560-1440.jpg)

Alex Higgins remains a national hero in Northern Ireland.

Image credit: Reuters

The term doesn’t apply in the truest form to O’Sullivan, world champion in 2001, 2004, 2008, 2012 and 2013. Not only is he popular with the public because of his voracious instinct to attack, but he is an out-and-out winner to encourage the theory that he is the greatest player to lift a cue.

Despite supporting Davis as a kid, O’Sullivan feels snooker would have struggled without the influence of Higgins as he explains here.

“I always remember Higgins being the people's champion and everybody rooting for him to win, but I was a Steve Davis fan myself because I was growing up, and I obviously wanted to be a winner,“ O’Sullivan told Eurosport. “I wanted to win tournaments like Davis, who was the guy doing that.

I just think Alex was the best thing that's probably ever happened to snooker

“But Alex Higgins brought something to snooker that nobody could bring. He made snooker what it was, and turned snooker players into rock stars. Looking back at it, if there was one player responsible for making snooker big in the 1980s, it was definitely Alex Higgins.

“If Higgins hadn't been there, snooker wouldn't have been popular on the back of Steve Davis or Stephen Hendry, who were very reserved in comparison. I think people gravitated towards Alex Higgins, he was a showman, he had something about him: a charm, an aura - when he walked into the room you felt there was a presence in the room. The audience would feed off that.

“I remember watching him in the qualifiers in Blackpool when I was younger. It was sad in a way because he shouldn't have gone through that. Alex was master of his own downfall in many ways, but in many ways that's why you loved him because there no compromise. He was anti-establishment, living life by Alex's rules. I admire that in a human.

“I just think Alex was the best thing that's probably ever happened to snooker. I spent time with him when I was only 16 in Blackpool. I practised with him at the time, and I used to run out to get him a Guinness. He’d say: ‘Go and get me a Guinness’. I loved it at the time. I thought: ‘I’m Alex’s slave’. It gave me a buzz. Everybody wanted to get him a Guinness, but he chose me. I remember watching him. He would say to the referee Len Ganley in those little cubicles in Blackpool when he was trying to play: 'stand back, you’re a big man'.

“I remember laughing, thinking: 'go on Alex, you tell him'. He terrorised people, but thrived on it. He got a buzz out of it. He was incredible. I kind of copied his technique a little bit. He was a bit like the Ding Junhui on the shot, very compact, solid technique. He had a few bad habits where he moved on the shot, but he tended to move after the shot. He was a very good ball striker.“

6. The Higgins Paradox

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2017/04/13/2062360-43242687-2560-1440.png)

Alex Higgins - Hannah Carroll for Eurosport

Image credit: Eurosport

Higgins was a world champion but became the people’s champion because he was not perceived as a great winner, rather a great bloke in the eyes of the British public. If you had the option of going on a bender with Higgins or Davis, there would only be one winner. And it would not have been a man who was mockingly nicknamed Steve ‘Interesting’ Davis by the satirical programme Spitting Image. Davis was deemed to own the title deeds to boredom, his willingness to play safe representative of his perceived character deficiencies.

"He was seen as the 'wild man' of snooker; once he finished playing he was off partying," said Davis. "People's perception of me was once I'd finished playing I was put back in the box, and wound up ready for the next match. I wasn't going past 12 o'clock at night and a glass of hot milk before I went to bed was considered to be my drink of choice."

The years have been kind to the persona of Davis, who does a techno set as DJ Thundermuscle on a local station in Essex these days, but his game was admired rather than loved. Prone to moments of brilliance and bedlam, Higgins was feted by the public because of his seemingly carefree attitude to life.

Why would you hero worship somebody who if he wasn’t a snooker player, you would treat with contempt?

Studying some of the footage of the adoring crowds enveloping Higgins, White and O’Sullivan, it is not difficult to detect a very male vibe. Especially at the Masters in London. At times, it reminds you a bit of being at a Morrissey concert where grown men can’t wait to embrace their king. If Higgins was doing well, all was well in many people’s world because if such a figure was able to succeed in snooker, it made one feel better about the possibilities in their own life.

Davis was the sport’s dominant force, nicknamed 'The Nugget' because according to Hearn "you could put your case of money on him, and you knew you were going to get paid". But it didn't make him likeable. "How do you identify with perfection?" is perhaps the most poignant question.

Higgins was viewed as the moral winner, and a genuine force of nature amid the saturated coverage. It is a phenomenon that the erudite cue sports commentator and writer Phil Yates, who began covering snooker in 1988, contributing heavily to The Times, continues to find baffling.

“There was a genuine dislike between Davis and Higgins. They were two completely different characters, but I think it was symptomatic of British society then and indeed now,” opines Yates. “Here is a bloke (Davis) who has done nothing wrong. A good clean living bloke, who doesn’t drink to excess, doesn’t smoke, doesn’t gamble, doesn’t do drugs. Just a normal working class bloke who by the majority of the people watching was demonised and victimised as being the baddie. On the other hand, you had someone who had every fault in the book, and every character flaw going, who was lionised and loved by the public. I think: Would that happen anywhere else? What was coming into play was the underdog factor because everybody respected Davis and realised how good he was.

“Higgins was the underdog, but was also the anti-establishment. Why was the good guy not perceived as the good guy? Why would you hero worship somebody who if he wasn’t a snooker player, you would treat with contempt? Apart from pure snooker, I always wonder why was that the case? The bad boy-good boy divide was huge between those two.”

7. In Eye Of The Storm Comes Hurricane’s Finest Moment

Much is made of Higgins winning two world titles, and the moment he wails when his wife Lynn and toddler Lauren join him with the trophy at the Crucible in 1982, seconds after running in 135 to defeat the six-times champion Reardon. His stand-out success arguably came a year later against Davis in the UK Championship final at Preston’s Guild Hall.

"Davis sends spectators to sleep," said Higgins. "Spectators have no point of contact. How can you relate to a robot? I'd rather have a drink with Idi Amin."

"That was because Idi Amin would buy him more drinks,” was the Davis retort. Not bad for a robot.

Up north, Higgins appeared to be heading south as he trailed 7-0 to his foe. In the same year, he had been largely outclassed 16-5 by Davis in the semi-finals of the World Championship. Yet Higgins somehow managed to rally, winning eight of the next nine frames to level at 8-8. He moved 14-12 clear, but trailed 15-14 before trousering the final two frames to the delight of his public.

There are dates that tend to stand out in your childhood. Such was the popularity of snooker, this onlooker recalls standing as a kid at a football match between Morton and Hibernian in the Scottish Premier League when the tannoy announcer felt the need to let the fans know Davis led Higgins 6-1 in the 1984 UK final. Davis would find revenge with a 16-8 win, but it was suspected the scars of losing a 7-0 lead were a precursor for a bigger sense of dismay further down the line when he blew an 8-0 advantage in losing the 1985 World Championship final to Taylor. It was a contest full of ebb and flow watched by 18.5m on BBC2 beyond midnight, a record audience for the channel.

It remains a source of wonderful misery for Davis, who ironically earned more goodwill in defeat than any victory could have garnered.

8. The Beginning Of The End

It is said Steve Davis spent more time on television than the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher during the 1980s. In parts of the UK, he was also desperately more unpopular than her. Like Thatcher, Davis was very much an emblem of the UK establishment while Higgins railed against authority. It was all utter nonsense of course, but why let the truth spoil a good pantomime.

When Higgins stepped out at the Wembley Conference Centre for their match at the 1985 Masters in the round of 16, he was cheered into the venue with more fanfare then the boxer Frank Bruno. Local lad Davis was roundly booed in a match he would lose 5-4 after making a blunder on the final blue.

He was a genius. They are a dying breed in sport

“We are f*****g back,” bellowed Higgins amid being mobbed by his adoring public, a comment he denied making before being fined, one of numerous costly outbursts he totted up simply for having no self-restraint. The only problem being, he wasn’t back. Higgins would enjoy only one more win over Davis, in the last four of the Irish Masters later that year, before suffering 11 defeats out of their final 12 matches. There was a 4-4 draw in league format match in 1990 when both made two centuries. It was their final competition match with his demise highlighted by Davis’ dominance of the second half of the 1980s.

"Higgins thought 'you might be better than me, but I'm going to draw you into my world'," commented O’Sullivan. “I think Higgins would draw you into a battle, and out of your comfort zone. Davis was a much heavier scorer and more of a power player. Higgins had no right to beat Davis, but Higgins was a magician with a terrific knowledge of the table. He was a genius. In fact, I'd say he was the only genius to play snooker. You'll never see another Alex Higgins again. It is like George Best.

"He was a genius. They are a dying breed in sport. John McEnroe was one, Alex Higgins was one and George Best was one. The culture has changed, you wouldn't find that type of player playing snooker anymore. I think for the sport, it is important to have rivalry. No two players stand out in snooker at the moment. Not like Davis and Higgins.”

9. Nugget Reaps Rewards After Harvest Years

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2017/04/13/2062364-43242767-2560-1440.jpg)

Steve Davis - Hannah Carroll for Eurosport

Image credit: Eurosport

Steve Davis’ longevity and his longing to play snooker beyond his harvest years illustrates why he will be recalled as a pioneer. On several occasions form, technique and confidence appeared to desert him yet he still found a way to remain relevant. Around the millennium, Terry Griffiths, the 1979 world champion, urged him to retire because of his dwindling standards. Yet he did not submerge.

His greatest success, arguably greater than the six world titles, came in the 1997 Masters final when he recovered from trailing 8-4 to O’Sullivan in the final to complete a 10-8 win as a dose of his vintage returned to haunt the 21-year-old O’Sullivan. Davis won six straight frames to justify his iconic standing as a giant of the game. It was a final that saw the sport’s first streaker bound around before the 39-year-old Davis streaked to victory.

O'Sullivan said: "Steve was like a machine, he was clinical. He was like Tiger Woods in golf when he came along. He was just different, and could boss and dominate the competition. I never really played Steve in his prime, but I did play him at the Masters in 1997. I remember he played six unbelievable frames against me when I didn't really see a ball after leading 8-4. I remember thinking: ‘I'm not sure, I would have liked to have played him in the 1980s if that is how he played the game’. I'm glad I missed that one. I got John Higgins instead which was just as bad, but Davis was the ultimate professional. He was a machine.”

At the age of 48, Davis reached the final of the 2005 UK Championship, a tournament where he enjoyed his highest break of 145, against Stephen Maguire, since making the first televised maximum at the Lada Classic in 1982. He lost 10-6 to China's rising 18-year-old national icon Ding Junhui in the final. A 52-year-old Davis then completed an astonishing 13-11 win over the defending world champion John Higgins in 2010 to reach the quarter-finals at the Crucible as a reminder of just how pristine his levels were. It came 21 years after he demolished Parrott 18-3 for the last of his six world gongs.

"Davis to me was the hardest player to beat," says White, the oldest player on the snooker tour now at 57. "Even nowadays against O'Sullivan you will get chances. Selby is very similar to Davis, but for me Davis is still the man to beat. He was just so good at the all-round game. His positional play and long potting were superb when he was at his best. He says in commentary these days that he wouldn't be in the top 16. I don't know why he says that because he would easily be in the top eight. All day long."

10. The Importance Of Legacy

Every sports professional wants to leave a legacy, but for the most talented it is a genuinely viable aim. You witness it in Roger Federer’s joy in winning a 18th Grand Slam in tennis at the Australian Open in Melbourne. You see it in the Cristiano Ronaldo v Lionel Messi battle to be remembered as the greatest footballer in the world game. You understand it in Usain Bolt's gait since he obliterated the world 100m record at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing. In snooker, O'Sullivan will aim for two more world titles to equal Hendry's record.

Not all sportspeople get the chance to leave legacies, but Davis and Higgins have etched their own faces in the rockface. Davis finally retired in 2016 having spawned a generation of Davises. When you watch snooker today, Higgins remains a one-off.

“Higgins was not the best player in snooker history, he wasn’t even in the top five,” notes Yates. “But in terms of being the most influential player in helping with the game’s boom, he was number one. Without a doubt. He outstripped Reardon, John Spencer and even Jimmy White. Higgins was the most important figure in the game in the late 70s and early to mid-1980s.”

You need villains and heroes

Hearn feels the cultural significance of Higgins should not be lost, nor his approach.

“Alex played snooker the way he lived his life: he took risks,” says Hearn. “Today’s modern player is very much in the Steve Davis mould. Rock solid, but a little bit dull. The extravagant shots cost you money, not just in snooker. In many respects, it has driven the character and personality out of all professional sport. Alex Higgins wouldn’t survive in today’s world. Higgins would be beaten these days by kids you have never heard of because they are all very good. But they wouldn’t sell tickets or enjoy TV ratings like Alex Higgins.

“You need villains and heroes. Everybody had a soft spot for Alex because he was flawed. Alex had the vulnerability that women felt was attractive, that he was alone and needed looking after. He was only alone because nobody wanted to be with him.”

Higgins had charisma and knew how to manhandle a crowd, but was also bitter against perceived injustice.

Perhaps he viewed Davis as a figure who got rich on the back of his popularity. While he was key to giving snooker a glorious money-spinning profile, Davis was the main beneficiary from making winning as much of a habit as brushing your teeth in the morning. If Higgins wanted to be a successful gambler, he should have started betting on Davis. Impossible of course when you believe you are the greatest, but trying to rule snooker while battling drink problems and wretched behaviour - which included striking your partner with a hairdryer - made such ambition impossible.

It is a feat more difficult than attempting a 147 wearing a blindfold. Yet to Higgins, nothing felt impossible. And when he had his day in the sun, he basked in it. In the previously hushed environs of snooker, he stood out because he was some sort of visionary in how to keep tabloid newspapers brimming with sozzled tales of woe. He made snooker front page news.

"The thrill of playing him was fantastic," Davis once said. "I used to be quite frightened of him as an individual. He could be quite vexatious. But on the snooker table, my admiration was immense.’’

11. A Loss Of Character

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2017/04/13/2062428-43244047-2560-1440.jpg)

The coffin of former world snooker champion Alex Higgins is carried from St Anne's Cathedral after a service, Belfast, Northern Ireland August 2, 2010

Image credit: Reuters

Where there is a lot of drink, there is not a lot of happiness. The World Championship was heavily funded by Embassy cigarettes throughout its heyday. It encouraged a culture of machismo, of smoking and heavy boozing that gave Higgins a platform. When cigarette sponsorship was finally outlawed after the smoking ban in 2005, snooker suffered serious financial withdrawals that it only began to recover from when Hearn returned to run the sport ten years ago, producing a tour that is no longer dependent upon interest in Britain.

It could be argued that access to alcohol and ciggies helped create inebriated monsters like Higgins, but booze was already part of the culture of working men in billiards halls before the TV cameras shone a light on it. It was a moment in time that officially glamourised damage to your health. And it was all there in front of millions watching on telly. For his part, 'Romford Slim' Davis could have been sponsored by the health board.

“Characters die out when technical ability in any sport increases,” says Hearn. “Today, we sell snooker on technical excellence. Sportspeople spend so much time interacting with themselves that they really don’t know or need to sell themselves to the public. Golfers spend nine hours a day hitting golf balls. All that matters is knocking it 300 yards down the middle, and planting it on the green. Process and repeat. That doesn’t give you much time to entertain a crowd. Are there any golfers around like Lee Trevino or Seve Ballesteros? A loss of character is not an issue only for snooker.”

The critics of snooker claim the game is no longer attractive because there is no longer anything they can relate to, no identity to grab onto. Dewy eyed and perhaps longing for the loss of their younger self, they claim snooker died when men liked Alex Higgins died out. But this is not snooker’s problem. As O’Sullivan points out here, Higgins reminds you a lot of the demise of his fellow Northern Irishman George Best. Football is no longer a forum for George Bests. Or Paul Gascoignes. And we should all be thankful for that.

Higgins enjoyed legendary boozing sessions with the likes of the late actor Oliver Reed, who was half cut when he appeared on This Is Your Life in 1981 to salute his drinking buddy Higgins, a bloke he claimed once necked a bottle of aftershave before him. But Higgins died long before his time. While Davis retired last year at the age of 57 after 38 years, around £25m in earnings, taking in inflation, and 28 ranking titles, his old rival blew his career earnings, battled depression, alcoholism, a 60-a-day cigarette habit and had two failed marriages on his way to a bitter, pitiful, penniless ending.

If it hadn’t have been for Alex, none of us would be here today

He will not be about to ever witness the bastion of snooker at the Crucible when he should be celebrated for giving lifeblood and meaning to the modern game.

Hendry, who replaced Higgins as snooker’s youngest world champion by a year at the age of 21 in 1990 on his way to a record haul of seven, told Higgins’ second wife at his funeral: “If it hadn’t have been for Alex, none of us would be here today". He said in an interview: "I was actually disappointed with the low turnout of top snooker players at the funeral. I think a lot of them don't appreciate how good he was and what he did for our sport."

If there were a snooker Mount Rushmore, perhaps etched on the seven hills of Sheffield, Davis and Higgins' places would be assured.

Amid the fug of smoke, and the unruly behaviour that would shame a dog, Higgins gave Davis a purpose, carried snooker beyond the confines of darkened rooms and unwittingly encouraged the advent of professional snooker despite treating his profession with utter disregard. He leaves a rich legacy. One lesson being on how not to live your life, but another suggesting that he was a true original of the species.

Unlike Davis, who strained every sinew to maximise his talent, Higgins fell short of what his natural ability hinted at.

“I wish I had six Alex Higgins these days, but I have to make do with one Ronnie O’Sullivan. They drive you crazy, but any sport really needs these type of characters. They are a dying breed,” said Hearn.

Davis will rightly be remembered as one of snooker’s great champions, perhaps the greatest winner, but Higgins is hardly a pauper in comparison. An anti-hero who was loved and loathed in various degrees, he will be recalled more fondly in death than he was in life.

“When they made the Hurricane, they must have broken the mould,” said Higgins. “I'm a one-off, a mystery man that would drive the world's most eminent psychiatrist to his consulting couch."

China has usurped the UK as the sport's most avid supporter base with 210 million enthusiasts clamping themselves to Ding's run to the 2016 World Championship final, but in a land of 1.35 billion it will not produce another Higgins. From its invention in India to its return to Asia, there are millions in the Far East who will never know of Higgins. Nor would they have understood what his purpose was amid the ongoing assault on the senses. Yet he was as vital to snooker as the balls and sticks.

Without the Guinness-guzzling, wild-eyed ‘Hurricane’ causing chaos, hitting out on and off the table and his fabled rivalry with Davis, snooker's quite astonishing narrative would never have possessed the building blocks to make it back out of Blighty.

Artwork by Phil Galloway and Hannah Carroll

Scan me

Related Topics

Share this article

Advertisement

Advertisement