The Essential Stories: One heartbeat from immortality - the Mike Marsh story

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2013/03/27/978647-15979742-310-310.jpg)

Updated 15/11/2019 at 08:48 GMT

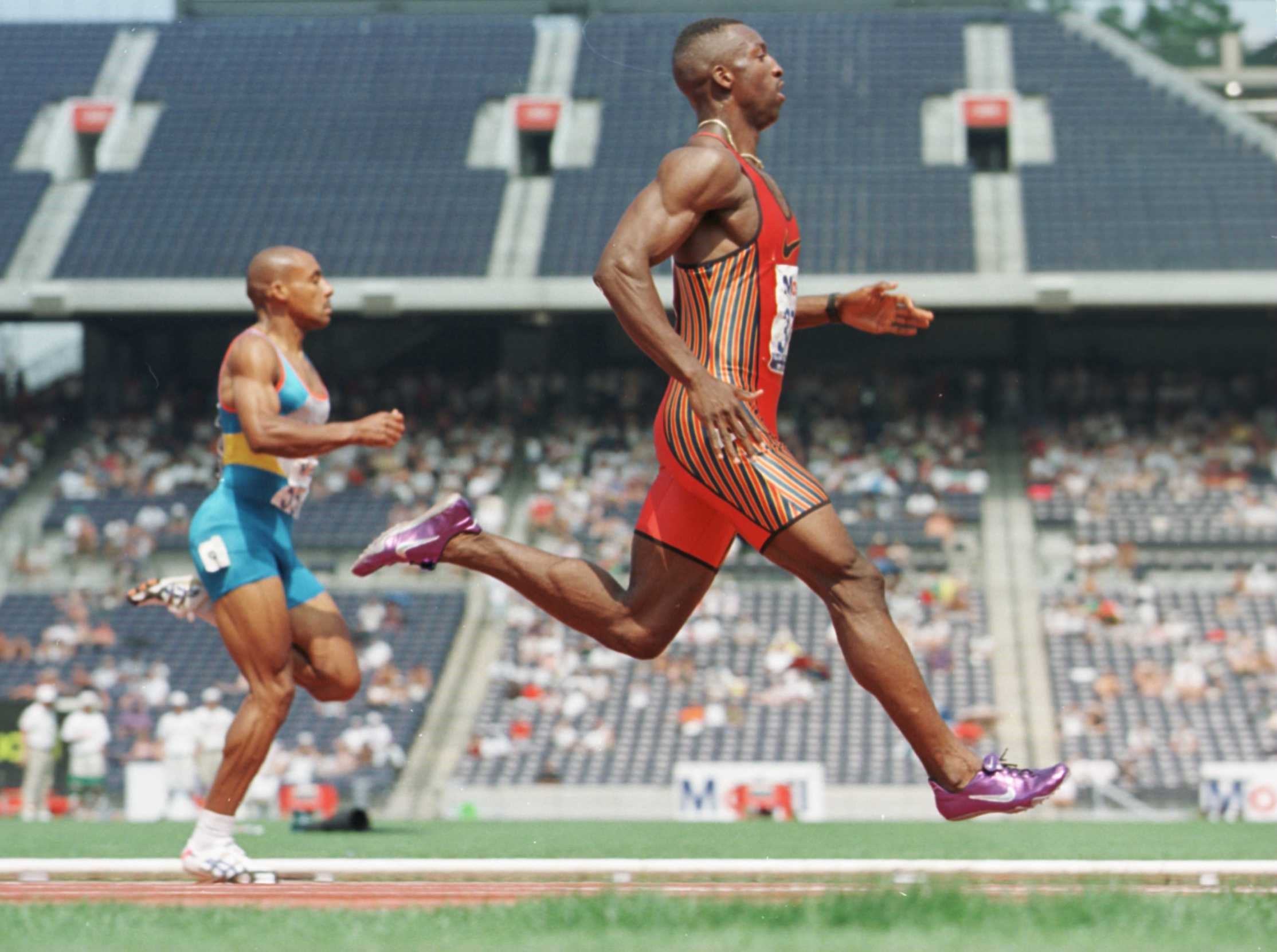

On August 5, 1992 in Barcelona, Mike Marsh should have beaten Pietro Mennea's fabled 13-year 200 metres world record.

Mike Marsh

Image credit: Eurosport

But during an Olympic semi-final he utterly dominated, Marsh was unaware that he was knocking on the door of greatness. By slowing down with the finish line gaping, he let a moment of history slip between his fingers. Here is the story of a missed opportunity for athletic immortality...

August 1, 1996. Atlanta. Centennial Olympic Stadium. History made in a moment of magic.

It's the final of the 200 metres. In lane three, with golden spikes and a matching gold necklace hanging around his neck, Michael Johnson prepares to complete a half-circuit of the track quicker than you can say Jack Robinson. The starter raises his pistol towards the sky and squeezes the trigger. The American fires from the blocks like a bullet. Known as 'The Duck' for his distinctive upright running style, Johnson leaves his competitors floundering in his wake. His upper body erect, and with a short, almost robotic stride, he gobbles up the Tartan. Exiting the bend, he enters a home straight that will take him to infinity and back.

Already a six-time world champion, Johnson has never been crowned Olympic champion in an individual event. It takes him just 19:32 seconds to rectify this anomaly. The time is worth repeating: 19:32.

"19:32? That's not a time – that's my dad's birthday," laughed Ato Boldon, bronze medallist of a race in which he became a mere footnote. That despite his own sizzling time of 19:80. It's fair to say that MJ set a stratospheric new benchmark that night.

Five days after Donovan Bailey's supersonic 100 metres, which plunged U.S. sprinting into darkness by repatriating the world record (9:84 seconds) north of the Canadian border, Johnson turned the power back on, producing a monumental electrical surge that could be seen from space. The Texan had already beaten the long-standing record of Pietro Mennea one month earlier, at the same location during the U.S. Championships (19:66). This time, he pulverized it. Johnson surpassed the Italian and his 1979 milestone by four-tenths of a second. In a world where Usain Bolt had yet to celebrate his tenth birthday, this time of 19:32 seemed forever unattainable. Yet the Jamaican would beat it, 12 years later, in the Beijing Games in a time of 19:30. And it would be seriously trounced when another lightning Bolt struck Berlin soil in 2009 (19:19).

The golden age of American sprinting

But Johnson, the hero of this August evening in 1996, is not the main protagonist of this story. At Atlanta, our subject finds himself out of the spotlight, at the back of the stage, practically relegated to the wings. Mike Marsh – for he's the sprinter in question – finished eighth in the 200 metres final with a time of 20:48. It was a catastrophic time, unworthy of the defending champion that he was.

At least he got a good view of history in the making: being in the inside lane, he witnessed MJ's meteoric run in all its glory. Although, given the eventual gap between the two men, the view could have been better. Marsh had just lost his Olympic title and, with it, any remaining hope of setting a world record for 200 metres. Almost 29 years old, the sprinter was on the downward slope of a career under which he would draw a line before the end of the twentieth century, crowned with two Olympic titles and a silver medal. As well as a missed opportunity to go down in posterity.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2019/09/27/2684779-55517890-2560-1440.jpg)

Mike Marsh at the Santa Monica Track Club

Image credit: Getty Images

Unlike many other champions, Michael Marsh, known simply as Mike, was not always on the path to greatness. He was an excellent athlete, there was no doubt. But excellence is not enough when your career collides with the golden age of American sprinting; when, unfortunately, your training buddies – members of the legendary Santa Monica Track Club – happen to be called Carl Lewis or Leroy Burrell and exchange 100-metre world records like other people exchange pleasantries. As for the 200 metres, Marsh found himself with Michael Johnson snapping at his heels.

At the heart of this constellation of talents, Marsh embodied an athlete with a human face. No lucrative advertising contracts, no sponsorship deals with equipment manufacturers to show off: he was just a regular fast guy who didn't sway his shoulders or run with a swagger.

Opportunity knocks, Marsh fails to open the door

In sprinting, as in history, timing is everything. There are those who are slow out of the blocks; those who start fast, then fade; those who show promise but pull up short; those who surprise; those who fail to capitalise and let an opportunity go begging.

In the summer of 1992, Mike Marsh was not exactly late for his day of destiny, it was history which turned up a fraction too early. A day too early, to be precise, in the semi-final of the Olympic Games. It was as if greatness came calling, but Marsh was looking the other way. And so an opportunity for athletic immortality passed him by. And for Mike Marsh, such an opportunity would not arrive again.

Marsh was Californian through and through. Born on August 4, 1967 in the heart of the Golden State and the sprawling, confusing City of Angels, the future double Olympic champion was the son of an estate agent and a chartered accountant. His childhood was ordinary and largely uneventful. Except that the kid ran fast and took up athletics in year six. Rightly so. He was naturally talented, clearly one of the best. But he was not the best. At Hawthorne High School, he lived in the shadow of a certain Henry Thomas.

If the name Henry Thomas doesn't mean much to most people, it's entirely understandable. He never made it big and, once grown up, would spend more time behind bars than on the track. Nevertheless, in the beginning of the 1980s, he was the terror of the local high schools – and some. Capable of running the 100 metres in 10:27, Thomas held the U18 world record for a decade. Given that, 35 years later, the reference mark is still only 10:15, this was no mean feat. He was just too strong, too early. And he didn't have the patience to stick it out.

The Los Angeles Olympics… as a volunteer

The only time Marsh emerged from his rival's shadow was the day Henry Thomas was laid low by appendicitis. Buoyed by his absence, Marsh won the CIF California State Meet 200 metres. Crowned with this title, he enrolled at UCLA. His university career was marked only by one minor stroke of brilliance: third place in the 100 metres during the NCAA university championships in 1987. His best times at university? 10:07 and 20:35. Good, but not good enough.

At this point in his career, Marsh's only experience of the Olympic Games was as a volunteer at the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984. These were the Games of King Carl, the quadruple gold medallist, when the young Mike Marsh was a parking attendant in Long Beach, where the fencing and volleyball events took place. Four years later, Marsh was substitute in the U.S. relay team at the 1988 Seoul Olympics. But the Americans were disqualified in the first round without him even putting on his spikes.

Three years later, the focus shifted to Tokyo and the World Championships. This time, Marsh took to the track. As part of the USA's 4x400 metres team, he broke the World Championship record in the heats (37:75). But he was not selected for the final, where the Americans put the French back in their place thanks to a world record time of 37:50.

Almost 25 years old, Marsh's career had yet to come out of the blocks. The athlete then made the best decision of his career: he left California and his coach John Smith for Texas, where he put his fate in the hands of Tom Tellez, who would take him to the next level.

1992: Marsh's transformation

The impact of this change was felt as early as the spring of 1992. Marsh ran the 100 metres in 9:93 (when the world record was still 9:86) and posted a time of 19:94 over 200 metres (when anything under the 20-second barrier was considered a milestone). Things were shaping up pretty well for the Barcelona Games. Even if the man himself remained cautious.

"I haven't done anything yet," Marsh said. "These are just two races. Now, I've got to repeat these performances when there's a gold medal at stake, against the big boys and under the spotlight." With excellent timing came the US Championships. For the first time, they also doubled up as the U.S. Olympic Trials, further increasing the pressure.

Marsh was right to be on his guard. In New Orleans, the venue for the important meet, his stellar spring times counted for nothing. The fact that he had posted the best performance in the world over 100 metres that year was irrelevant. For here he only mustered fourth place and duly missed out on qualification for the Games. He was not the only one. Proving that even the best are not untouchable, an ill Carl Lewis, winner of the five previous World and Olympic titles, came sixth and failed to make the cut. He would never run another Olympic 100 metres again. Dennis Mitchell, Mark Witherspoon and Leroy Burrell were selected.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2019/09/27/2684783-55517970-2560-1440.jpg)

Mike Marsh lors des Trials 1992

Image credit: Getty Images

Marsh made up for things in the 200 metres in what proved to be a supersonic final. A favourable tailwind (one metre per second) helped his cause, and that of winner Michael Johnson, who was crowned champion of the United States. With times of 19:79 and 19:86, both men had made a statement. They also became respectively the fourth and fifth fastest athletes in history over 200 metres. Their next showdown was pencilled in for Catalonia.

But it never happened. In Barcelona, Marsh was crowned Olympic champion in a tight final in a time of 20:01 – a final without Michael Johnson.

MJ down for the count

To complete his preparation, Johnson had gone to Salamanca. Two weeks before the Games, MJ, who had forgone the 400 metres to focus fully on the 200 metres, went out for dinner with his agent, Clyde Hart. The two men were initially tempted to give into a guilty pleasure: a good old Burger King, just like back home. But in the end, they opted for a nice local restaurant called El Candil, where they'd eaten the night before. Down on his luck, MJ ate something dodgy and contracted food poisoning. Even before the torch had been lit at the Montjuic Stadium, Michael Johnson had effectively losts.

During the first two heats, he managed to disguise his loss of strength from the virus. But the semi-final proved a step too far. He came sixth in a time of 20:78 and was eliminated. This would have been a huge thunderclap had lightning not struck Catalonia just a few minutes before. Because as MJ was still tying his shoelaces, the enthralled spectators in the Estadio Olimpic were still coming to terms with Marsh's own semi-final performance, which had come within a hair's breadth of perfection.

The greatest 200 metres in history for 190 metres

It's the first semi-final on August 5, 1992. In lane five Mike Marsh runs at the speed of light. Flawlessly, he takes the bend and, entering the home straight, he's streets ahead of the field. Britain's Linford Christie, running on empty following his surprise win in the 100 metres, is a mere shadow as Marsh surges clear, distancing him in his wake. Peerless on the track, Marsh's biggest opponent is himself: he does not realise a mythical record is within touching distance.

He's so strong that he relaxes his effort, decelerates inside the final 10 metres and crosses the line before coming to a standstill. He raises his eyes towards heaven, and then towards the billboard showing his time: 19:73. 19:73? Correct: 19:73. Judging by the look in his eyes, it's clear that he's torn between satisfaction for having done the job, and incomprehension – emphasised by the number of times his gaze, as if magnetised, returns to the screen. Marsh has just run one of the greatest 200 metres in history. Without knowing it. He has failed to beat the world record by a tiny hundredth of a second – and not just any record, but that of Pietro Mennea.

For 13 years, the Italian's benchmark had stood the test of time. To the extent that it seemed immoveable, set in stone. When Michael Johnson eventually managed to wipe the slate clean, Mennea would admit: "I never thought that my record would last so long. At the time, I did not even think I had run so fast."

Mennea – grasping the unreachable

Carl Lewis wanted to be the one to show that the Italian had indeed not run so fast – that his inaccessible record was accessible. No other reference mark had stood as long as Mennea's over 200 metres. The benchmark of 19:72 seconds became an obsession for Lewis, as much as the monumental 8.90 metres of Bob Beamon's jump of the century. Mennea's record, which was achieved at altitude, where the air resistance was less, during the Mexico City Universiade Games of 1979, always eluded King Carl.

Despite this fixation, for a long time Lewis refused on principle to compete at altitude simply to have a better shot at breaking the record. In 1983, he had even skipped a meet – the U.S. Olympic Festival – held at Colorado Springs, at 1,839 metres above sea level. Calvin Smith, on the other hand, went up there and broke the 100 metres world record in a time of 9:93. Evelyn Ashford did the same for the women (10:79).

At sea level, the same year, Lewis should have beaten Mennea's time during the U.S. Championships. But, five metres from the finish, sure of his victory and with a whiff of arrogance that he could afford to show, he had begun to celebrate with the Indianapolis crowd. The result: 19:75 seconds – a new U.S. record.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2019/09/30/2686970-55561710-2560-1440.jpg)

Carl Lewis

Image credit: Getty Images

At the time, Lewis was only 22 years old. When it came to breaking the record, everyone felt that it was not a question of if, but when. Lewis, however, would never run quicker than that time in Indianapolis. He would never beat Mennea. No more than he would ever (legally, that is) jump farther than Beamon, whose record was eventually superseded, right under Lewis' eyes, and quite unexpectedly, by Mike Powell at the end of the most thrilling long jump contest in history. (The 1991 World Championships in Tokyo, where Powell beat Beamon's jump by 5cm for a record which still stands today – moments after Lewis had jumped one centimetre longer than Beamon, but wind-aided.)

In Barcelona, it was not arrogance that dashed Marsh's dreams. The Californian simply managed his efforts. He did what every athlete would have done. He was ahead, he had qualified for the final, he kept some juice in the tank. It was that simple. "To be honest, I did this time a little bit by accident," he said afterwards. "I did not know what I was doing. I just ran and, at the finish, asked myself: 'Wow, what did you just do?'"

"But why did you slow down, you fool?"

Speaking to the Los Angeles Times one year after his pulsating run, Marsh said: "I have no regrets. I simply followed the instructions of coach Tellez. It was clear: if I was ahead, I was supposed to slow down to keep something back for the final. How could I have known that I was about to run 19:73? I had no idea of my speed and of the fact that I was going so fast."

He then added these words, seeped in remorse: "Sometimes, though, I catch myself thinking back and I say to myself, 'But why did you slow down, you fool?' But I can't change anything. That's life."

On August 6, the day of the Olympic final, Mike Marsh climbs up Montjuic Hill to the Olympic Stadium with a firm idea in his head: take the title, for sure, but this time, dislodge Mennea from his pedestal. Michael Johnson is out of the picture, Frankie Fredericks, already a silver medallist behind Christie in the 100 metres, is there for the taking.

Marsh does not leave the blocks as well as the day before, but he still exits the bend in the lead. And this time, he continues his effort right to the finish. Fredericks returns towards the end, but it's the American who crosses the line ahead of everyone. He comes to rest with his hands on his hips, looking at the billboard. The same fixed look as the day before. He does not celebrate, and his face displays no emotion, even though he's just become Olympic champion. Looking closer into his eyes, however, it is easy to see that he is scrutinizing something else. 20:01. An unfavourable wind of one metre. He enters the history books, sure. But immortality has slipped through his fingers.

For the first 190 metres of his fateful semi-final, Marsh had put in the best performance ever seen in the 200 metres. Using an anemometer to consider a slight adverse wind of -0.2m/s, unofficial split analysis shows that he would have crossed the line in a time of 19:65 had he not cut short his effort…

"I put a lot of years into this and it finally paid off," he said stoically after the final. "I did not run as quick as I would have liked, but I won the gold medal and that's the most important thing. After my 19:73 in the semis, of course I was thinking that I could break the world record today. But I was more tired than I imagined. I'm unhappy that I didn't run harder and get the world record in the semi-finals. But world records come and go, and I've got the gold medal in my pocket."

Mike Marsh was not wrong. But he could not help but think that on the day of the biggest potential heist of the century, he fled the bank having left some of the loot in the safe.

/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2019/09/27/2684788-55518070-2560-1440.jpg)

Mike Marsh, sacré champion olympique du 200m en 1992

Image credit: Getty Images

Written by Maxime Dupuis, translated by Felix Lowe

Scan me

Related Topics

Share this article

Advertisement

Advertisement